Benjamin Mountfort

Background Information

This Wikipedia selection is available offline from SOS Children for distribution in the developing world. Click here to find out about child sponsorship.

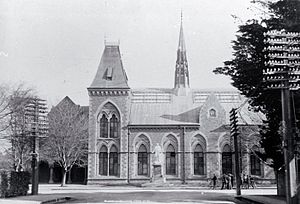

Benjamin Woolfield Mountfort ( 13 March 1825– 15 March 1898) was an English emigrant to New Zealand, where he became one of that country's most prominent 19th century architects. He was instrumental in shaping the city of Christchurch. He was appointed the first official Provincial Architect of the developing province of Canterbury. Heavily influenced by the Anglo-Catholic philosophy behind early Victorian architecture he is credited with importing the Gothic revival style to New Zealand. His Gothic designs constructed in both wood and stone in the province are considered unique to New Zealand. Today he is considered the founding architect of the province of Canterbury.

Early life

Mountfort was born in Birmingham, an industrial city in the Midlands of England, the son of perfume manufacturer Thomas Mountfort and his wife Susanna (née Woolfield). As a young adult he moved to London, where he studied architecture under the Anglo-Catholic architect Richard Cromwell Carpenter, whose medieval Gothic style of design was to have a lifelong influence on Mountfort. After completion of his training, Mountfort practised architecture in London. Following his 1849 marriage to Emily Elizabeth Newman, the couple emigrated in 1850 as some of the first settlers to the province of Canterbury, arriving on one of the famed "first four ships", the Charlotte-Jane. These first settlers, known as "The Pilgrims", have their names engraved on marble plaques in Cathedral Square, Christchurch, in front of the cathedral that Mountfort helped to design.

New Zealand

In 1850 New Zealand was a new country. The British government actively encouraged emigration to the colonies, and Mountfort arrived in Canterbury full of ambition and drive to begin designing in the new colony. With him and his wife from England came also his brother Charles, his sister Susannah, and Charles' wife, all five of them aged between 21 and 26. Life in New Zealand at first was hard and disappointing: Mountfort found that there was little call for architects. Christchurch was little more than a large village of basic wooden huts on a windswept plain. The new emigré's architectural life in New Zealand had a disastrous beginning. His first commission in New Zealand was the Church of the Most Holy Trinity in Lyttelton, which collapsed in high winds shortly after completion. This calamity was attributed to the use of unseasoned wood and his lack of knowledge of the local building materials. Whatever the cause, the result was a crushing blow to his reputation. A local newspaper called him:

… a half-educated architect whose buildings… have given anything but satisfaction, he being evidently deficient in all knowledge of the principles of construction, though a clever draughtsman and a man of some taste..

Consequently, Mountfort left architecture and ran a bookshop while giving drawing lessons until 1857. It was during this period in the architectural wilderness that he developed a lifelong interest in photography and supplemented his meagre income by taking photographic portraits of his neighbours. Mountfort was a Freemason and an early member of the Lodge of Unanimity, and the only building he designed during this period of his life, in 1851, was its lodge. This was the first Masonic lodge in the South Island.

Return to architecture

In 1857 he returned to architecture and entered into a business partnership with his sister Susannah's new husband, Isaac Luck. Christchurch, which was given city status in July 1856 and was the administrative capital of the province of Canterbury, was heavily developed during this period. The rapid development in the new city created a large scope for Mountfort and his new partner. In 1858 they received the commission to design the new Canterbury Provincial Council Buildings, a stone building today regarded as one of Mountfort's most important works. The building's planning stage began in 1861, when the Provincial Council had grown to include 35 members and consequently the former wooden chamber was felt to be too small.

The new grandiose plans for the stone building included not only the necessary offices for the execution of council business but also dining rooms and recreational facilities. From the exterior, the building appears austere, as was much of Mountfort's early work: a central tower dominates two flanking gabled wings in the Gothic revival style. However the interior was a riot of colour and medievalism as perceived through Victorian eyes; it included stained glass windows, and a large double-faced clock, thought to be one of only five around the globe. The chamber is decorated in a rich, almost Ruskinesque style, with carvings by a local sculptor William Brassington. Included in the carvings are representations of indigenous New Zealand species.

This high-profile commission may seem surprising, bearing in mind Mountfort's history of design in New Zealand. However, the smaller buildings he and Luck had erected the previous year had impressed the city administrators and there was a dearth of available architects. The resultant acclaim of the building's architecture marked the beginning of Mountfort's successful career.

Mountfort's Gothic architecture

The Gothic revival style of architecture began to gain in popularity from the late 18th century as a romantic backlash against the more classical and formal styles which had predominated the previous two centuries. At the age of 16, Mountfort acquired two books written by the Gothic revivalist Augustus Pugin: The True Principles of Christian or Pointed Architecture and An Apology for the Revival of Christian Architecture. From this time onwards, Mountfort was a disciple of Pugin's strong Anglo-Catholic architectural values. These values were further cemented in 1846, at the age of 21, Mountfort became a pupil of Richard Cromwell Carpenter.

Carpenter was, like Mountfort, a devout Anglo-Catholic and subscribed to the theories of Tractarianism, and thus to the Oxford and Cambridge Movements. These conservative theological movements taught that true spirituality and concentration in prayer was influenced by the physical surroundings, and that the medieval church had been more spiritual than that of the early 19th century. As a result of this theology, medieval architecture was declared to be of greater spiritual value than the classical Palladian-based styles of the 18th and early 19th centuries. Augustus Pugin even pronounced that medieval architecture was the only form suitable for a church and that Palladianism was almost heretical. Such theory was not confined to architects, and continued well into the 20th century. This school of thought led intellectuals such as the English poet Ezra Pound, author of The Cantos, to prefer Romanesque buildings to Baroque on the grounds that the latter represented an abandonment of the world of intellectual clarity and light for a set of values that centred around hell and the increasing dominance of society by bankers, a breed to be despised.

Whatever the philosophy behind the Gothic revival, in London the 19th-century rulers of the British Empire felt that Gothic architecture was suitable for the colonies because of its then strong Anglican connotations, representing hard work, morality and conversion of native peoples. The irony of this was that many of Mountfort's churches were for Roman Catholics, as so many of the new immigrants were of Irish origin. To the many middle-class English empire builders, Gothic represented a nostalgic reminder of the parishes left behind in Britain with their true medieval architecture; these were the patrons who chose the architects and designs.

Mountfort's early Gothic work in New Zealand was of the more severe Anglican variety as practised by Carpenter, with tall lancet windows and many gables. As his career progressed, and he had proved himself to the employing authorities, his designs developed into a more European form, with towers, turrets and high ornamental roof lines in the French manner, a style which was in no way peculiar to Mountfort but was endorsed by such architects as Alfred Waterhouse in Britain. On the other hand, the French chateaux style was always more popular in the colonies than in Britain, where such monumental buildings as the Natural History Museum and St Pancras Station were subject to popular criticism. In the United States, however, it was adopted with huge enthusiasm, with families such as the Vanderbilts lining 5th Avenue in New York City with many Gothic chateaux and palaces.

Mountfort's skill as an architect lay in adapting these flamboyant styles to suit the limited materials available in New Zealand. While wooden churches are plentiful in certain parts of the USA, they are generally of a simple classic design, whereas Mountfort's wooden churches in New Zealand are as much ornate Gothic fantasies as those he designed in stone. Perhaps the flamboyance of his work can be explained in a statement of principles he and his partner Luck wrote when bidding to win the commission to design Government House, Auckland in 1857:

...Accordingly, we see in Nature's buildings, the mountains and hills; not regularity of outline but diversity; buttresses, walls and turrets as unlike each other as possible, yet producing a graduation of effect not to be approached by any work, moulded to regularity of outline. The simple study of an oak or an elm tree would suffice to confute the regularity theory. 2

This seems to be the principle of design that Mountfort practised throughout his life.

Provincial Architect

As the "Provincial Architect" — a newly created position to which Mountfort was appointed in 1864 — Mountfort designed a wooden church for the Roman Catholic community of the city of Christchurch. This wooden erection was subsequently enlarged several times until it was renamed a cathedral. It was eventually replaced in 1901 by the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament, a more permanent stone building by the architect Frank Petre. Mountfort often worked in wood, a material he in no way regarded as an impediment to the Gothic style. It is in this way that many of his buildings have given New Zealand its unique Gothic style. Between 1869 and 1882 he designed the Canterbury Museum and subsequently Canterbury College and its clock tower in 1877.

Construction on the buildings for the Canterbury College, which later became the University of Canterbury, began with the construction of the clock tower block. This edifice, which opened in 1877, was the first purpose built university in New Zealand. The College was completed in two subsequent stages in Mountfort's usual Gothic style. The completed complex was very much, as intended, an architectural rival to the expansions of the Oxbridge Colleges simultaneously being built in England. Built around stone courtyards, the high Victorian collegiate design is apparent. Gothic motifs are evident in every facade, including the diagonally rising great staircase window inspired by the medieval chateau at Blois. The completed composition of Canterbury College is very reminiscent of Pugin's convent of "Our Lady of Mercy" in Mountfort's home town of Birmingham, completed circa 1843, a design that Mountfort would probably have been familiar with as a boy. It is through the College buildings, and Mountfort's other works, that Canterbury is unique in New Zealand for its many civic and public buildings in the Gothic style.

George Gilbert Scott, the architect of Christchurch Cathedral, and an empathiser of Mountfort's teacher and mentor Carpenter, wished Mountfort to be the clerk of works and supervising architect of the new cathedral project. This proposal was originally vetoed by the Cathedral Commission. Nevertheless, following delays in the building work attributed to financial problems, the position of supervising architect was finally given to Mountfort in 1873. Mountfort was responsible for several alterations to the absentee main architect's design, most obviously the tower and the west porch. He also designed the font, the Harper Memorial, and the north porch. The cathedral was however not finally completed until 1904, six years after Mountfort's death. The cathedral is very much in the European decorated Gothic style with an attached campanile tower beside the body of the cathedral, rather than towering directly above it in the more English tradition. In 1872 Mountfort became a founding member of the Canterbury Association of Architects, a body which was responsible for all subsequent development of the new city. Mountfort was now at the pinnacle of his career.

By the 1880s, Mountfort was hailed as New Zealand's premier ecclesiastical architect, with over forty churches to his credit. In 1888, he designed St John's Cathedral in Napier. This brick construction was demolished in the disastrous 1931 earthquake that destroyed much of Napier. Between 1886 and 1897, Mountfort worked on one of his largest churches, the wooden St Mary's, the cathedral church of Auckland. Covering 9000 square feet (800 m²), St Mary's is the largest wooden Gothic church in the world. The custodians of this white-painted many-gabled church today claim it to be one of the most beautiful buildings in New Zealand. In 1982 the entire church, complete with its stained glass windows, was transported to a new site, across the road from its former position where a new cathedral was to be built. St Mary's church was consecrated in 1898, one of Mountfort's final grand works.

Outside of his career, Mountfort was keenly interested in the arts and a talented artist, although his artistic work appears to have been confined to art pertaining to architecture, his first love. He was a devout member of the Church of England and a member of many Anglican church councils and diocese committees. Mountfort's later years were blighted by professional jealousies, as his position as the province's first architect was assailed by new and younger men influenced by new orders of architecture. Benjamin Mountfort died in 1898, aged 73. He was buried in the cemetery of Holy Trinity, Avonside, the church which he had extended in 1876.

Evaluation of Mountfort's work

Evaluating Mountfort's works today, one has to avoid judging them against a background of similar designs in Europe. In the 1860s, New Zealand was a developing country, where materials and resources freely available in Europe were conspicuous by their absence. When available they were often of inferior quality, as Mountfort discovered with the unseasoned wood in his first disastrous project. His first buildings in his new homeland were often too tall, or steeply pitched, failing to take account of the non-European climate and landscape. However, he soon adapted, and developed his skill in working with crude and unrefined materials.

Christchurch and its surrounding areas are unique in New Zealand for their particular style of Gothic architecture, something that can be directly attributed to Benjamin Mountfort. While Mountfort did accept small private domestic commissions, he is today better known for the designs executed for public, civic bodies, and the church. His monumental Gothic stone civic buildings in Christchurch, which would not be out of place in Oxford or Cambridge, are an amazing achievement over adversity of materials. His hallmark wooden Gothic churches today epitomise the 19th-century province of Canterbury. They are accepted, and indeed appear as part of the landscape. In this way, Benjamin Mountfort's achievement was to make his favoured style of architecture synonymous with the identity of the province of Canterbury. Following his death, one of his seven children, Cyril, continued to work in his father's Gothic style well into the 20th century. Cyril Mountfort was responsible for the church of "St. Luke's in the City" which was an unexecuted design of his father's. In this way, and through the daily public use of his many buildings, Mountfort's legacy lives on. He ranks today with his contemporary R A Lawson as one of New Zealand's greatest 19th century architects.

Buildings by Benjamin Mountfort

- Most Holy Trinity in Lyttelton, 1851 (demolished)

- Canterbury Provincial Council Buildings, 1858–1865:

- Christchurch Cathedral, begun 1863:

- Canterbury Museum, 1869–1882:

- St. Augustine's Church, Waimate 1872:

- Trinity Church, Christchurch 1873:

- Avonside Church Chancel, 1876:

- St Paul's Church, Papanui, 1877

- Canterbury College, Christchurch, 1882:

- Church of the Good Shepherd, Phillipstown,1884

- St Mary's Church, Auckland, begun 1886: .

- St John's Cathedral, Napier, 1888

- Sunnyside Asylum, Christchurch, 1881–1893