Dayuan

Did you know...

SOS Children offer a complete download of this selection for schools for use on schools intranets. SOS mothers each look after a a family of sponsored children.

The Dayuan or Ta-Yuan (Chinese: 大宛; pinyin: Dàyuān; Wade–Giles: Ta-Yuan, lit. “Great Yuan”) were a people of Ferghana in Central Asia, described in the Chinese historical works of Records of the Grand Historian and the Book of Han, which follow the travels of Chinese explorer Zhang Qian in 130 BCE and the numerous embassies that followed him into Central Asia thereafter. The country of Dayuan is generally accepted as relating to the Ferghana Valley.

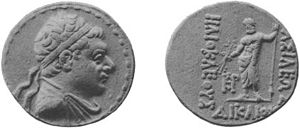

These Chinese accounts describe the Dayuan as urbanized dwellers with Caucasian features, living in walled cities and having "customs identical to those of the Greco-Bactrians", a Hellenistic kingdom that was ruling Bactria at that time in today’s northern Afghanistan. The Dayuan are also described as manufacturers and great lovers of wine.

The Dayuan were probably the descendants of the Greek colonies that were established by Alexander the Great in Ferghana in 329 BCE, and prospered within the Hellenistic realm of the Seleucids and Greco-Bactrians, until they were isolated by the migrations of the Yuehzhi around 160 BCE. It has also been suggested that the name “Yuan” was simply a transliteration of the words “ Yona”, or “ Yavana”, used throughout antiquity in Asia to designate Greeks (“ Ionians”), so that Dayuan (lit. “Great Yuan”) would mean "Great Ionians".

The interaction between the Dayuan and the Chinese is historically crucial, since it represents one of the first major contacts between an urbanized Indo-Iranian culture and the Chinese civilization, opening the way to the formation of the Silk Road that was to link the East and the West in material and cultural exchange from the 1st century BCE to the 15th century.

Hellenistic rule (329–160 BCE)

The region of Ferghana was conquered by Alexander the Great in 329 BCE and became his most advanced base in Central Asia. He founded the fortified city of Alexandria Eschate (Lit. “Alexandria the Furthest”) in the southwestern part of the Ferghana valley, on the southern bank of the river Syr Darya (ancient Jaxartes), at the location of the modern city of Khujand (also called Khozdent, formerly Leninabad), in the state of Tajikistan. Alexander built a 6 kilometer long brick wall around the city and, as for the other cities he founded, had a garrison of his retired veterans and wounded settle there.

The whole of Bactria, Transoxiana and the area of Ferghana remained under the control of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire until 250 BCE. The region then wrested independence under the leadership of its governor Diodotus of Bactria, to become the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom.

Greco-Bactrian kingdom (250–160 BCE)

The Greco-Bactrians held their territory, and according to the Greek historian Strabo even went beyond Alexandria Eschate and "extended their empire as far as the Seres (China) and the Phryni" ( Strabo XI.XI.I). There are indications that they may have led expeditions as far as Kashgar in Xinjiang, leading to the first known contacts between China and the West around 200 BC. Various statuettes and representations of Greek soldiers have been found north of the Tien Shan, and are today on display in the museum of Urumqi (Boardman).

Around 160 BC, the area of Ferghana seems to have been invaded by Saka tribes (called the Sai-Wang by the Chinese). The Sai-Wang, originally settled in the Ili valley in the general area of Lake Issyk Kul, were retreating southward after having been dislodged by Yuezhi (who themselves were fleeing from the Xiongnu):

- "The Yuezhi attacked the king of the Sai ("Sai-Wang") who moved a considerable distance to the south and the Yuezhi then occupied his lands" (Han Shu, 61 4B).

The Sakas occupied the Greek territory of Dayuan, benefiting from the fact that the Greco-Bactrians were fully occupied with conflicts in India against the Indo-Greeks, and could hardly defend their northern provinces. According to W.W.Tarn, "The remaining of the Sai-Wang tribes apparently seized the Greek province of Ferghana… It was easy at this time to occupy Ferghana: Eucratides had just overthrown the Euthydemid dynasty, he himself was with his army in India, and in 159 he met his death… Heliocles, preoccupied first with the recovery of Bactria and then with the invasion of India, must have let this outlying province go" (W.W.Tarn, "The Greeks in Bactria and India").

Saka rule (160 BCE onward)

When the Chinese envoy Zhang Qian described Dayuan around 128 BCE, he mentioned, besides the flourishing urban civilization, warriors "shooting arrows on horseback", a probable description of Saka nomad warriors. Dayuan had probably by then become a caste of nomadic people ruling over a pre-existing agricultural population.

Also in 106–101 BCE, during their conflict against China, the country of Dayuan is said to have been an ally with the neighbouring tribes of the Kang-Kiu ( Sogdians). The Chinese also record the name of the king of Dayuan as "Mu-Kua", a Saka name rendered in Greek as Mauakes or Maues (another Scythian ruler by the name of Maues is known as a ruler of the Indo-Scythian kingdom in northern India in the 1st century BCE).

Yuezhi by-pass (155 BCE)

According to the Han Chronicles the Yuezhi suffered another defeat around 155 BCE, against the Wusun, and fled south from the Ili river area, by-passed the urban civilization of the Dayuan in Ferghana, and re-settled north of the Oxus in modern-day Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, definitively cutting Dayuan from contact with the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. The Yuezhi would further expand southward into Bactria around 125 BCE, and then going on to form the Kushan Empire in India from the 1st century CE.

Interaction with China (130 BCE onward)

The Dayuan remained a healthy and powerful civilization which had numerous contacts and exchanges with China from 130 BCE.

Around 130 BCE, at the time of Zhang Qian’s embassy to Central Asia, the Dayuan were described as inhabitants of a region corresponding to the Ferghana, to the west of the Chinese empire. “The capital of the kingdom of Dayuan is the city of Guishan ( Khujand), distant from Chang'an 12,550 li. The kingdom contains 60,000 families, comprising a population of 300,000, with 60,000 trained troops, a Viceroy, and a National Assistant Prince. The seat of the Governor General lies to the east at a distance of 4,031 li.” (Han Shu)

To their south-west were the territories of the Yuezhi, with the Greco-Bactrians further south still, beyond the Oxus. “The great Yueh-chih is situated about 2000 or 3000 li west of Dayuan; they dwell north of the river Kuei ( Oxus). To the south of them there is Daxia ( Bactrians), to the west, Anxis ( Parthians); to the north Kangju ( Sogdians).” ( Shiji, 123.5b)

The Shiji then explains that the Yueh-Chih originally inhabited the area East of the Dayuan, in the Tarim Basin, before they suffered a crushing defeat against the Xiongnu and their leader Mao-tun in 176 BCE, forcing them to go beyond the territory of the Dayuan and resettle in the West by the banks of the Oxus, between the territory of the Dayuan and Bactria to the south.

Urbanized city-dwellers

The customs of the Dayuan are said by Zhang Qian to be identical to those of the Bactrians in the south, who actually formed the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom at that time.

“Their customs (the Bactrians) are the same as those of Dayuan. The people have fixed abodes and live in walled cities and regular houses like the people of Dayuan. They have no great kings or heads, but everywhere in their walled cities and settlements they have installed small kings.” ( Shiji, 123.3b)

They are described as town-dwellers, as opposed to other populations such as the Yuezhi, the Wun-Sun or the Xiongnu who were nomads. “They (the Dayuan) have walled cities and houses; the large and small cities belonging to them, fully seventy in number, contain an aggregate population of several hundreds of thousands…There are more than seventy other cities in the country.” (Han Shu)

Appearance and Culture

The Shiji comments on the Caucasian-like appearance and the culture of the people around Dayuan: “The peoples west of Dayuan to Anxi (Parthia) have deep sunken eyes, and bushy beards and whiskers. They are clever traders, and dispute about the division of a farthing. Women are honorably treated among them, and their husbands are guided by them in their decisions.” ( Shiji, 123)

They were great manufacturers and lovers of wine, a characteristic often associated with Greeks: “Round about Dayuan they make wine from grapes. Wealthy people store up as much as 10,000 stones and over in their cellars, and keep it for several tens of years without spoiling. The people are fond of wine.” ( Shiji, 123).

Influence

According to the Shiji, grapes and alfalfa were introduced to China from Dayuan following Zhang Qian's embassy:

-

- "The regions around Dayuan make wine out of grapes, the wealthier inhabitants keeping as much as 10,000 or more piculs stored away. It can be kept for as long as twenty or thirty years without spoiling. The people love their wine and the horses love their alfalfa. The Han envoys brought back grape and alfalfa seeds to China and the emperor for the first time tried growing these plants in areas of rich soil. Later, when the Han acquired large numbers of the "heavenly horses" and the envoys from foreign states began to arrive with their retinues, the lands on all sides of the emperor's summer palaces and pleasure towers were planted with grapes and alfalfa for as far as the eye could see."

The Shiji also claims that metal casting was introduced to the Dayuan region by Han deserters: "... the casting of coins and vessels was formerly unknown. Later, however, when some of the Chinese soldiers attached to the Han embassies ran away and surrendered to the people of the area, they taught them how to cast metal and manufacture weapons."

Relations with China

Following the reports of Zhang Qian (who was originally sent to obtain an alliance with the Yuezhi against the Xiongnu, in vain), the Chinese emperor Wudi became interested in developing commercial relationships with the sophisticated urban civilizations of Ferghana, Bactria and Parthia: “The Son of Heaven on hearing all this reasoned thus: Ferghana (Dayuan) and the possessions of Bactria and Parthia are large countries, full of rare things, with a population living in fixed abodes and given to occupations somewhat identical with those of the Chinese people, but with weak armies, and placing great value on the rich produce of China” ( Shiji, 123)

The Chinese subsequently sent numerous embassies, around ten every year, to these countries and as far as Seleucid Syria. “Thus more embassies were dispatched to An-si [ Parthia], An-ts'ai [the Aorsi, or Alans], Li-kan [Syria under the Seleucids], T'iau-chi [ Chaldea], and Shon-tu [India]… As a rule, rather more than ten such missions went forward in the course of a year, and at the least five or six.” ( Shiji, 123)

The Chinese were also strongly attracted by the tall and powerful horses ("heavenly horses") in the possession of the Dayuan, which were of capital importance to fight the nomad Xiongnu. The refusal of the Dayuan to offer them enough horses along with a series of conflicts and mutual disrespect resulted in the death of the Chinese ambassador and the confiscation of the gold send as payment for the horses.

Enraged, the Chinese Emperor sent an army in 104 BC/BCE under general Li Guangli. They failed, essentially through lack of preparation and because they underestimated their adversaries: “The army of Yuan is weak; if we attack it with no more than three thousand Chinese soldiers using crossbows, we shall be sure to vanquish it completely.” ( Shiji, 123)

Emperor Wudi then sent a second army of 100,000 men to subdue Dayuan, believing than had the Chinese Empire fails to demonstrate its might to a small nation as Dayuan, her ambassadors will not be treated with respect among the various nations of the west in the future.(indeed Chinese records state that in contrast to the Xiongnu Ambassadors, Chinese ambassadors were forced to pay for their own food and mount.)

Finally obtained 3,000 horses through negotiation, although they did not manage to take the Dayuan capital: “On its arrival there the Chinese army consisted of thirty thousand men. An army of Yuan gave battle, the victory being gained by the efficiency of the Chinese archery; and this caused the Yuan army to take refuge in their bulwarks and mount the city walls… After all, the Chinese were unable to enter the inner city, and, abandoning further action, the army was led back.” ( Shiji, 123) Despite the victories the Chinese army suffered heavy causalities, largely as it seemed, from mistreatment of the Chinese commanders, as the Chinese records suggest that only a small number were slain in battles and the army had been relatively well supplied. Indeed the incompentence of general Li Guangli stood out among the many excellent commanders that had served China during Wudi’s reign.

Contacts with the West were re-established following the peace treaty with the Yuan. Ambassadors were once again sent to the West, caravans were sent to Bactria.

An era of East-West trade and cultural exchange

The Silk Road essentially came into being from the 1st century BC/BCE, following the efforts of China to consolidate a road to the Western world, both through direct settlements in the area of the Tarim Basin and diplomatic relations with the countries of the Dayuan, Parthians and Bactrians further west.

Intense trade followed soon, confirmed by the Roman craze for Chinese silk (supplied by the Parthians) from the 1st century BC, to the point that the Senate issued, in vain, several edicts to prohibit the wearing of silk, on economic and moral grounds. This is attested by at least three significant authors:

- Strabo (64/ 63 BCE–c. 24 CE).

- Seneca the Younger (c. 3 BCE–65 CE).

- Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE).

This is also the time when the Buddhist faith and the Greco-Buddhist culture started to travel along the Silk Road, penetrating China from around the 1st century BCE.