Italian language

Did you know...

The articles in this Schools selection have been arranged by curriculum topic thanks to SOS Children volunteers. SOS Child sponsorship is cool!

| Italian | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italiano, Lingua italiana | ||||

| Pronunciation | [itaˈljaːno] | |||

| Native to | Italy, San Marino, Malta, Switzerland, Vatican City, Slovenia ( Slovenian Istria), Croatia ( Istria County), Argentina, Brazil, Australia | |||

| Region | (widely known among older people and in commercial sectors in Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Libya; used in the Federal Government of Somalia) | |||

| Native speakers | 61 million Italian proper, native and native bilingual (2007) 85 million all varieties |

|||

| Language family |

Indo-European

|

|||

| Writing system | Latin ( Italian alphabet) Italian Braille |

|||

| Official status | ||||

| Official language in | ||||

| Regulated by | not officially by Accademia della Crusca | |||

| Language codes | ||||

| ISO 639-1 | it | |||

| ISO 639-2 | ita | |||

| ISO 639-3 | ita | |||

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-q | |||

|

||||

Italian (italiano or lingua italiana) is a Romance language spoken mainly in Europe: Italy, Switzerland, San Marino, Vatican City, by minorities in Malta, Monaco, Croatia, Slovenia, France, Libya, Eritrea, and Somalia, and by expatriate communities in the Americas and Australia. Many speakers are native bilinguals of both standardised Italian and other regional languages.

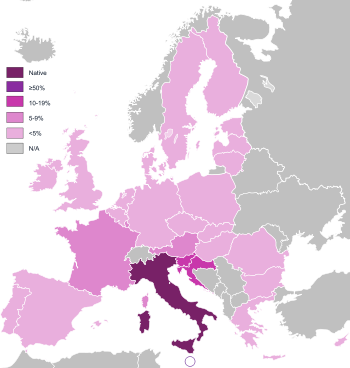

According to the Bologna statistics of the European Union, Italian is spoken as a mother tongue by 59 million people in the EU (13% of the EU population), mainly in Italy, and as a second language by 14 million (3%). Including the Italian speakers in non-EU European countries (such as Switzerland and Albania) and on other continents, the total number of speakers is more than 85 million.

In Switzerland, Italian is one of four official languages; it is studied and learned in all the confederation schools and spoken, as mother language, in the Swiss cantons of Ticino and Grigioni and by the Italian immigrants that are present in large numbers in German- and French-speaking cantons. It is also the official language of San Marino, as well as the primary language of Vatican City. It is co-official in Slovenian Istria and in Istria County in Croatia. The Italian language adopted by the state after the unification of Italy is based on Tuscan, which beforehand was a language spoken mostly by the upper class of Florentine society. Its development was also influenced by other Italian languages and by the Germanic languages of the post-Roman invaders.

Italian is descended from Latin. Unlike most other Romance languages, Italian retains Latin's contrast between short and long consonants. As in most Romance languages, stress is distinctive. In particular, among the Romance languages, Italian is the closest to Latin in terms of vocabulary.

History

The standard Italian language has a poetic and literary origin starting in the twelfth century, and the modern standard of the language was largely shaped by relatively recent events. However, Italian as a language used in the Italian Peninsula has a longer history. In fact the earliest surviving texts that can definitely be called Italian (or more accurately, vernacular, as distinct from its predecessor Vulgar Latin) are legal formulae from the Province of Benevento that date from 960–963. What would come to be thought of as Italian was first formalized in the early fourteenth century through the works of Tuscan writer Dante Alighieri, written in his native Florentine. Dante's epic poems, known collectively as the Commedia, to which another Tuscan poet Giovanni Boccaccio later affixed the title Divina, were read throughout Italy and his written dialect became the "canonical standard" that all educated Italians could understand. Dante is still credited with standardizing the Italian language, and thus the dialect of Florence became the basis for what would become the official language of Italy.

Italian often was an official language of the various Italian states predating unification, slowly usurping Latin, even when ruled by foreign powers (such as the Spanish in the Kingdom of Naples, or the Austrians in the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia), even though the masses spoke primarily vernacular languages and dialects. Italian was also one of the many recognised languages in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Italy has always had a distinctive dialect for each city, since the cities, until recently, were thought of as city-states. Those dialects now have considerable variety. As Tuscan-derived Italian came to be used throughout Italy, features of local speech were naturally adopted, producing various versions of Regional Italian. The most characteristic differences, for instance, between Roman Italian and Milanese Italian are the gemination of initial consonants and the pronunciation of stressed "e", and of "s" in some cases: e.g. va bene "all right": is pronounced [va ˈbːɛne] by a Roman (and by any standard-speaker), [va ˈbene] by a Milanese (and by any speaker whose native dialect lies to the north of La Spezia–Rimini Line); a casa "at home" is [a ˈkːasa] for Roman and standard, [a ˈkaza] for Milanese and generally northern.

In contrast to the Northern Italian language, southern Italian dialects and languages were largely untouched by the Franco- Occitan influences introduced to Italy, mainly by bards from France, during the Middle Ages but, after the Norman conquest of southern Italy, Sicily became the first Italian land to adopt Occitan lyric moods (and words) in poetry. Even in the case of Northern Italian language, however, scholars are careful not to overstate the effects of outsiders on the natural indigenous developments of the languages.

The economic might and relatively advanced development of Tuscany at the time ( Late Middle Ages) gave its dialect weight, though the Venetian language remained widespread in medieval Italian commercial life, and Ligurian (or Genoese) remained in use in maritime trade alongside the Mediterranean. The increasing political and cultural relevance of Florence during the periods of the rise of Medici's bank, Humanism, and the Renaissance made its dialect, or rather a refined version of it, a standard in the arts.

Renaissance

Starting with the Renaissance Italian became the language used in the courts of every state in the peninsula. The rediscovery of Dante's De vulgari eloquentia and a renewed interest in linguistics in the sixteenth century, sparked a debate that raged throughout Italy concerning the criteria that should govern the establishment of a modern Italian literary and spoken language. Scholars divided into three factions:

- The purists, headed by Venetian Pietro Bembo (who, in his Gli Asolani, claimed the language might be based only on the great literary classics, such as Petrarch and some part of Boccaccio). The purists thought the Divine Comedy not dignified enough, because it used elements from non-lyric registers of the language.

- Niccolò Machiavelli and other Florentines preferred the version spoken by ordinary people in their own times.

- The courtiers, like Baldassare Castiglione and Gian Giorgio Trissino, insisted that each local vernacular contribute to the new standard.

A fourth faction claimed the best Italian was the one that the papal court adopted, which was a mix of Florentine and the dialect of Rome. Eventually, Bembo's ideas prevailed, and the foundation of the Accademia della Crusca in Florence (1582–1583), the official legislative body of the Italian language led to publication of Agnolo Monosini's Latin tome Floris italicae linguae libri novem in 1604 followed by the first Italian dictionary in 1612.

Modern era

An important event that helped the diffusion of Italian was the conquest and occupation of Italy by Napoleon in the early nineteenth century (who was himself of Italian-Corsican descent). This conquest propelled the unification of Italy some decades after, and pushed the Italian language into a lingua franca used not only among clerks, nobility and functionaries in the Italian courts but also in the bourgeoisie.

Contemporary times

Italian literature's first modern novel, I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed), by Alessandro Manzoni, further defined the standard by "rinsing" his Milanese "in the waters of the Arno" ( Florence's river), as he states in the Preface to his 1840 edition.

After unification a huge number of civil servants and soldiers recruited from all over the country introduced many more words and idioms from their home languages (" ciao" is derived from Venetian word "s-cia[v]o" (slave), " panettone" comes from Lombard word "panatton" etc.). Only 2.5% of Italy’s population could speak the Italian standardized language properly when the nation unified in 1861.

Classification

Italian is a Romance language; it derives diachronically from Latin. It is part of the Italic branch of the Indo-European language family. Italian is related most closely to the other two Italo-Dalmatian languages, Sicilian and the extinct Dalmatian.

Unlike most other Romance languages, Italian retains Latin's contrast between short and long consonants. As in most Romance languages, stress is distinctive. In particular, among the Romance languages, Italian is the closest to Latin in terms of vocabulary. Lexical similarity is 90% with French, 88% with Catalan, 85% with Sardinian, 82% with Spanish and Portuguese, 78% with Rhaeto-Romance, and 77% with Romanian.

Geographic distribution

Europe

Italian is the official language of Italy and San Marino and is spoken fluently by the majority of the countries' populations. Italian is official together with French, German and Romansch in Switzerland, with most of the 0.5 million speakers being concentrated in the south of the country in the cantons of Ticino and southern Graubünden. Italian is the third most spoken language in Switzerland (after German and French), and has modestly declined since the 1970s. Italian is also used in administration and official documents in Vatican City.

Italian is also widely spoken in Malta, where nearly two-thirds of the population can speak it fluently, making it the most spoken non-official language. It served as Malta's official language until 1934. Italian is also recognized as an official language in Istria County, Croatia and Slovenian Istria where there are significant and historic Italian populations.

Italian is also spoken in Dodecanese islands, mainly in Rhodes and Leros, former colonies from 1912 to 1945.

Italian is also spoken by a minority in Monaco and France (especially in the southeast of the country and Corsica). Small Italian-speaking minorities can also be found in Albania and Montenegro.

Africa

Due to heavy Italian influence during the Italian colonial period, Italian is still widely understood in the countries of Libya and Eritrea. Although it was the primary language since colonial rule, Italian greatly declined under the rule of Muammar Gaddafi, who expelled the Italian Libyan population and made Arabic the sole official language of the country. Nevertheless, Italian remains an important language in the education and economic sectors in Libya. In Eritrea, Italian is a principal language in commerce and the capital city Asmara still has an Italian-language school. Italian was also introduced to Somalia through colonialism and was the sole official language of administration and education during the colonial period but declined after government, educational and economic infrastructure was destroyed in the Somali Civil War. Italian remains spoken as a second language by the elderly and educated and is also used in the new Federal Government of Somalia.

Italian was also used in administration in Ethiopia when the country was briefly occupied by Italy from 1936 to 1941; nowadays, the language is spoken only by older people, because it is no longer taught in schools.

Immigrant communities

Although over 17 million Americans are of Italian descent, only a little over one million people in the United States speak Italian at home. Nevertheless, an Italian language media market does exist in the country.

In Canada, Italian is the second most spoken non-official language when Chinese dialects are not combined, with over 660,000 speakers (or about 2.1% of the population) according to the 2006 Census.

In Australia, Italian is the second most spoken foreign language after the Chinese languages, with 1.4% of the population speaking it as their home language.

Italian immigrants to South America have also brought a presence of the language to the continent. Italian is the second most spoken language in Argentina after the official language of Spanish, with 1.5 million speaking it natively, and Italian has also heavily influenced the dialect of Spanish spoken in Argentina and Uruguay, Rioplatense Spanish. Small Italian-speaking minorities on the continent are also found in Uruguay, Venezuela and Brazil.

Education

Italian is widely taught in many schools around the world, but rarely as the first foreign language; in fact, Italian is considered the fourth- or fifth-most frequently taught foreign language in the world.

According to the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, every year there are more than 200,000 foreign students that are learning Italian language; they are distributed in the 90 Institutes of Italian Culture in the world, in the 179 Italian schools abroad and in the 111 Italian sections that are open into foreign schools.

In the United States, Italian is the fourth most taught foreign language after Spanish, French and German, in that order (or the fifth if American Sign Language is considered). In anglophone Canada, Italian is the second-most taught language after French, while in the United Kingdom it is the fourth after French, Spanish and German. In central-east Europe Italian is first in Albania and Montenegro, second in Austria, Croatia, Slovenia, and Ukraine after English, and third in Hungary, Romania and Russia after English and German. But throughout the world, Italian is the fifth most taught foreign language, after English, French, German, and Spanish.

In the European Union statistics, Italian is spoken as a mother tongue by 13% of the population or 65 million people, mainly in Italy. In the EU, it is spoken as a second language by 3% of the population or by 14 million people. In addition, among EU states, the Italian language is most likely to be learned as a second language in Malta by 61% of the population, as well as in Slovenia by 15% of the population, in Croatia by 14% of the population, Austria by 11% of the population, Romania by 8% of the population, and in France and Greece by 6% of the population. Italian is also one of the national languages of Switzerland, which is not a part of the European Union. The Italian language is well-known and studied in Albania, another non-EU member, due to its historical ties and geographical proximity to Italy.

Influence and derived languages

From the late nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, thousands of Italians settled in Argentina, Uruguay, southern Brazil, and Venezuela, where they formed a strong physical and cultural presence.

In some cases, colonies were established where variants of regional (i.e. non-central) Italian languages were used, and some continue to use a derived dialect. Examples are Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, where Talian is used, and the town of Chipilo near Puebla, Mexico; each continues to use a derived form of Venetian dating back to the nineteenth century. Another example is Cocoliche, an Italian-Spanish pidgin once spoken in Argentina and especially in Buenos Aires, and Lunfardo.

Rioplatense Spanish, and particularly the speech of the city of Buenos Aires, has intonation patterns that resemble those of Italian languages, because Argentina has had a continuous large influx of Italian settlers since the second half of the nineteenth century: initially primarily from northern Italy; then, since the beginning of the twentieth century, mostly from southern Italy.

Lingua franca

Starting in late medieval times, Italian language variants replaced Latin to become the primary commercial language in much of Europe and the Mediterranean Sea (especially the Tuscan and Venetian variants). These variants were consolidated during the Renaissance with the strength of Italian and the rise of humanism in the arts.

During the Renaissance, Italy held artistic sway over the rest of Europe. All educated European gentlemen were expected to make the Grand Tour, visiting Italy to see its great historical monuments and works of art. It thus became expected that educated Europeans should learn at least some Italian; the English poet John Milton, for instance, wrote some of his early poetry in Italian. In England, Italian became the second most common modern language to be learned, after French (though the classical languages, Latin and Greek, came first). However, by the late eighteenth century, Italian tended to be replaced by German as the second modern language in the curriculum. Yet Italian loanwords continue to be used in most other European languages in matters of art and music.

Within the Catholic church, Italian is known by a large part of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, and is used in substitution for Latin in some official documents. The presence of Italian as the primary language in the Vatican City indicates use, not only within the Holy See, but also throughout the world where an episcopal seat is present. It continues to be used in music and opera. Other examples where Italian is sometimes used as a means of communication are in some sports (sometimes in football and motorsports) and in the design and fashion industries.

Italian dialects and languages

In Italy, almost all Romance languages spoken as the vernacular (other than standard Italian and other unrelated, non-Italian languages) are termed "Italian dialects"; the only exceptions are Sardinian and Friulan, which the law recognises as official regional languages.

Many Italian dialects may be considered historical languages in their own right. These include recognized language groups such as, Neapolitan, Sardinian, Sicilian, Ligurian, Piedmontese, Venetian, and others, and regional variants of these languages such as Calabrian. The distinction between dialect and language has been made by scholars (such as Francesco Bruni): on the one hand are the languages that made up the Italian koine; and on the other, those that had little or no part in it, such as Albanian, Greek, German, Ladin, and Occitan, which some minorities still speak. The Corsican language is also related to Italian.

Regional differences can be recognized by various factors: the openness of vowels, the length of the consonants, and influence of the local language (for example, in informal situations the contraction annà replaces andare in the area of Rome for the infinitive "to go"; and nare is what Venetians say for the infinitive "to go").

Phonology

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental/ Alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||

| Plosive | p b | t d | k ɡ | |||

| Affricate | ts dz | tʃ dʒ | ||||

| Fricative | f v | s z | ʃ | |||

| Trill | r | |||||

| Lateral | l | ʎ | ||||

| Approximant | j | w |

Italian has a typical Romance-language seven-vowel system, consisting of /a, ɛ, e, i, ɔ, o u/, as well as 23 consonants. Compared with most other Romance languages, Italian phonology is extremely conservative, preserving many words nearly unchanged from Vulgar Latin. Some examples:

- Italian quattordici "fourteen" < Latin quattuordecim (cf. Spanish catorce, French quatorze /kaˈtɔʁz/, Catalan catorze)

- Italian settimana "week" < Latin septimāna (cf. Spanish semana, French semaine /s(ǝ)ˈmɛn/, Catalan setmana)

- Italian medesimo "same" < Vulgar Latin *medi(p)simum (cf. Spanish mismo, French même /mɛm/, Catalan mateix; note that Italian usually uses the shorter stesso)

- Italian guadagnare "to win, earn" < Vulgar Latin *guadanyāre < Germanic /waidanjan/ (cf. Spanish ganar, French gagner /ɡaˈɲe/, Catalan guanyar)

The conservativeness of Italian phonology is partly explained by its origin. Italian stems from a literary language that is derived from the 13th-century speech of the city of Florence in the region of Tuscany, and has changed little in the last 700 years or so. Furthermore, the Tuscan dialect is the most conservative of all Italian dialects, radically different from the Gallo-Italian languages less than 100 miles to the north (across the La Spezia–Rimini Line).

The following are some of the conservative phonological features of Italian, as compared with the common Western Romance languages (French, Spanish, Portuguese, Galician, Catalan). Some of these features are also present in Romanian.

- Little or no lenition of consonants between vowels, e.g. vīta > vita "life" (cf. Spanish vida [biða], French vie), pedem > piede "foot" (cf. Spanish pie, French pied /pje/).

- Preservation of doubled consonants, e.g. annum > anno "year" (cf. Spanish año /aɲo/, French an /ɑ̃/).

- Preservation of all Proto-Romance final vowels, e.g. pacem > pace "peace" (cf. Spanish paz, French paix /pɛ/), octō > otto "eight" (cf. Spanish ocho, French huit), fēcī > feci "I did" (cf. Spanish hice, French fis /fi/).

- Preservation of intertonic vowels (those between the stressed syllable and either the beginning or ending syllable). This accounts for some of the most noticeable differences, as in the forms quattordici and settimana given above.

- Lack of various consonant "deformations", e.g. folia > Italo-Western /fɔʎʎa/ > foglia /fɔʎʎa/ "leaf" (cf. Spanish hoja /oxa/, French feuille /fœj/; but note Portuguese folha /foʎɐ/).

Compared with most other Romance languages, Italian has a large number of inconsistent outcomes, where the same underlying sound produces different results in different words, e.g. laxāre > lasciare and lassare, captiāre > cacciare and cazzare, (ex)dēroteolāre > sdrucciolare and druzzolare, rēgīna > regina and reina, -c- > /k/ and /g/, -t- > /t/ and /d/. This is thought to reflect the several-hundred-year period during which Italian developed as a literary language divorced from any native-speaking population, with an origin in 12th/13th-century Tuscan but with many words borrowed from languages farther to the north, with different sound outcomes. (The La Spezia–Rimini Line, the most important isogloss in the entire Romance-language area, passes only about 20 miles to the north of Florence.)

Some other features that distinguish Italian from the Western Romance languages:

- Latin ce-,ci- becomes /tʃe,tʃi/ rather than /(t)se,(t)si/.

- Latin -ct- becomes /tt/ rather than /jt/ or /tʃ/: octō > otto "eight" (cf. Spanish ocho, French huit).

- Vulgar Latin -cl- becomes cchi /kkj/ rather than /ʎ/: oclum > occhio "eye" (cf. Portuguese olho /oʎu/, French oeil /œj/ < /œʎ/).

- Final /s/ is not preserved, and vowel changes rather than /s/ are used to mark the plural: amico, amici "male friend(s)", amica, amiche "female friend(s)" (cf. Spanish amigo(s) "male friend(s)", amiga(s) "female friends"); trēs, sex > tre, sei "three, six" (cf. Spanish tres, seis).

Standard Italian also differs in some respects from most nearby Italian languages:

- Perhaps most noticeable is the total lack of metaphony, a feature characterizing nearly every other Italian languages.

- No simplification of original /nd/, /mb/ (which often became /nn/, /mm/ elsewhere).

Writing system

The Italian alphabet has only 21 letters. The letters ⟨j, k, w, x, y⟩ are excluded, though they appear in loanwords such as jeans, whisky and taxi. The letter ⟨x⟩ has become common in standard Italian with the prefix extra-, although (e)stra- is traditionally used. The letter ⟨j⟩ originated as an archaic orthographic variant of ⟨i⟩. It appears in the first name Jacopo and in some Italian place-names, such as Bajardo, Bojano, Joppolo, Jerzu, Jesolo, Jesi, Ajaccio, among numerous others. It also appears in Mar Jonio, an alternative spelling of Mar Ionio (the Ionian Sea). The letter ⟨j⟩ may appear in dialectal words, but its use is discouraged in contemporary standard Italian. The foreign letters can be substituted with phonetically equivalent native Italian letters and digraphs: ⟨gi⟩ or ⟨ge⟩ for ⟨j⟩; ⟨c⟩ or ⟨ch⟩ for ⟨k⟩ (including in the standard prefix kilo-); ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩ or ⟨v⟩ for ⟨w⟩; ⟨s⟩, ⟨ss⟩, ⟨z⟩, ⟨zz⟩ or ⟨cs⟩ for ⟨x⟩; and ⟨e⟩ or ⟨i⟩ for ⟨y⟩.

- The acute accent is used over ⟨e⟩ to indicate a stressed front close-mid vowel, as in perché "why, because". In dictionaries, it is also used over ⟨o⟩ to indicate a stressed back close-mid vowel (azióne). The grave accent is used over ⟨e⟩ to indicate a front open-mid vowel, as in tè "tea". The grave accent is used over any vowel to indicate word-final stress, as in gioventù "youth". Unlike ⟨é⟩, a stressed final ⟨o⟩ is always a back open-mid vowel (andrò), making ⟨ó⟩ unnecessary outside of dictionaries. Most of the time, the penultimate syllable is stressed. But if the stressed vowel is the final letter of the word, the accent is mandatory, otherwise it is not (unlike in Spanish) and virtually always omitted. Exceptions are typically either in dictionaries, where all stressed vowels are commonly marked if they are either in a syllable other than the penultimate, or are an e or an o; or for disambiguating words that differ only by stress, as for prìncipi "princes" and princìpi "principles". For monosyllabic words, the rule is different: when two identical monosyllabic words with different meanings exist, the accent is compulsory on one and forbidden on the other (example: è "is", e "and"). Rare, polysyllabic words can have doubtful stress. Istanbul can be accented on the first (Ìstanbul) or second syllable (Istànbul). The U.S. state name Florida is pronounced in Italian as in Spanish with stress on the second syllable (Florìda). Because of an Italian word with the same spelling but different stress (flòrida "flourishing") and because of the English pronunciation, most Italians pronounce Florida with stress on the first syllable. Dictionaries give the latter as an alternative pronunciation.

- The letter ⟨h⟩ distinguishes ho, hai, ha, hanno (present indicative of avere "to have") from o ("or"), ai ("to the"), a ("to"), anno ("year"). In the spoken language, the letter is always silent. The ⟨h⟩ in ho additionally marks the contrasting open pronunciation of the ⟨o⟩. The letter ⟨h⟩ is also used in combinations with other letters. No phoneme [h] exists in Italian. In nativised foreign words, the ⟨h⟩ is silent. For example, hotel and hovercraft are pronounced /oˈtɛl/ and /ˈɔverkraft/ respectively. (Where ⟨h⟩ existed in Latin, it either disappeared or, in a few cases before a back vowel, changed to [g]: traggo "I pull" < Lat. trahō.)

- The letters ⟨s⟩ and ⟨z⟩ can symbolize voiced or voiceless consonants. ⟨z⟩ symbolizes /dz/ or /ts/ depending on context, with few minimal pairs. For example: zanzara /dzanˈdzaːra/ "mosquito" and nazione /natˈtsjoːne/ "nation". ⟨s⟩ symbolizes /s/ word-initially before a vowel, when clustered with a voiceless consonant (⟨p, f, c, ch⟩), and when doubled; it symbolizes /z/ when between vowels and when clustered with voiced consonants. Intervocalic ⟨s⟩ varies regionally between /s/ and /z/.

- The letters ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ vary in pronunciation between plosives and affricates depending on following vowels. The letter ⟨c⟩ symbolizes /k/ when word-final and before the back vowels ⟨a, o, u⟩. It symbolizes / tʃ/ as in chair before the front vowels ⟨e, i⟩. The letter ⟨g⟩ symbolizes /ɡ/ when word-final and before the back vowels ⟨a, o, u⟩. It symbolizes / dʒ/ as in gem before the front vowels ⟨e, i⟩. Other Romance languages and, to an extent, English have similar variations for ⟨c, g⟩. Compare hard and soft C, hard and soft G. (See also palatalization.)

- The digraphs ⟨ch⟩ and ⟨gh⟩ indicate or preserve hardness (/k/ and /ɡ/) before ⟨i, e⟩. The digraphs ⟨ci⟩ and ⟨gi⟩ indicate or preserve softness (/tʃ/ and /dʒ/) before ⟨a, o, u⟩. For example:

-

Before back vowel (A, O, U) Before front vowel (I, E) Plosive C caramella /karaˈmɛlla/ candy CH china /ˈkina/ India ink G gallo /ˈɡallo/ rooster GH ghiro /ˈɡiro/ edible dormouse Affricate CI ciaramella /tʃaraˈmɛlla/ shawm C Cina /ˈtʃina/ China GI giallo /ˈdʒallo/ yellow G giro /ˈdʒiro/ round, tour

- Note: ⟨h⟩ is silent in the digraphs ⟨ch⟩, ⟨gh⟩; and ⟨i⟩ is silent in the digraphs ⟨ci⟩ and ⟨gi⟩ before ⟨a, o, u⟩ unless the ⟨i⟩ is stressed. For example, it is silent in ciao /ˈtʃa.o/ and cielo /ˈtʃɛ.lo/, but it is pronounced in farmacia /ˌfar.maˈtʃi.a/ and farmacie /ˌfar.maˈtʃi.e/.

Italian has geminate, or double, consonants, which are distinguished by length and intensity. Length is distinctive for all consonants except for /ʃ/, /ts/, /dz/, /ʎ/, /ɲ/, which are always geminate, and /z/, which is always single. Geminate plosives and affricates are realised as lengthened closures. Geminate fricatives, nasals, and /l/ are realized as lengthened continuants. There is only one vibrant phoneme /r/ but the actual pronunciation depends on context and regional accent. Generally one can find a flap consonant [ɾ] in unstressed position while [r] is more common in stressed syllables, but there may be exceptions. Especially people from the Northern part of Italy ( Parma, Aosta Valley, South Tyrol) may pronounce /r/ as [ʀ], [ʁ], or [ʋ].

Of special interest to the linguistic study of Italian is the gorgia toscana, or "Tuscan Throat", the weakening or lenition of certain intervocalic consonants in the Tuscan language.

The voiced postalveolar fricative /ʒ/ is only present in loanwords: for example, garage [ɡaˈraːʒ].

Assimilation

Italian phonotactics do not usually permit verbs and polysyllabic nouns to end with consonants, excepting poetry and song, so foreign words may receive extra terminal vowel sounds.

Grammar

Italian grammar is typical of the grammar of Romance languages in general. Cases exist for pronouns ( nominative, oblique, accusative, dative), but not for nouns. There are two genders (masculine and feminine). Nouns, adjectives, and articles inflect for gender and number (singular and plural). Adjectives are sometimes placed before their noun and sometimes after. Subject nouns generally come before the verb. Subjective pronouns are usually dropped, their presence implied by verbal inflections. Noun objects come after the verb, as do pronoun objects after imperative verbs and infinitives, but otherwise pronoun objects come before the verb. There are numerous contractions of prepositions with subsequent articles. There are numerous productive suffixes for diminutive, augmentative, pejorative, attenuating etc., which are also used to create neologisms.

There are three regular sets of verbal conjugations, and various verbs are irregularly conjugated. Within each of these sets of conjugations, there are four simple (one-word) verbal conjugations by person/number in the indicative mood ( present tense; past tense with imperfective aspect, past tense with perfective aspect, and future tense), two simple conjugations in the subjunctive mood (present tense and past tense), one simple conjugation in the conditional mood, and one simple conjugation in the imperative mood. Corresponding to each of the simple conjugations, there is a compound conjugation involving a simple conjugation of "to be" or "to have" followed by a past participle.

Examples

Conversation

| English (inglese) | Italian (italiano) | Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | Sì | ( listen) /si/ |

| No | No | ( listen) /nɔ/ |

| Of course! | Certo! / Certamente! / Naturalmente! | |

| Hello! | Ciao! (informal) / Salve! (general) | e lei (Formal)( listen) /ˈtʃao/ |

| Cheers! | Salute! | /saˈlute/ |

| How are you? | Come stai? (informal) / Come sta? (formal) / Come state? (plural) / Come va? (general) | /ˈkomeˈstai/ ; /ˈkomeˈsta/ |

| Good morning! | Buon giorno! (= Good day!) | /bwɔnˈdʒorno/ |

| Good evening! | Buona sera! | /bwɔnaˈsera/ |

| Good night! | Buona notte! (for a good night sleeping) / Buona serata! (for a good night awake) | |

| Have a nice day! | Buona giornata! (formal) | |

| Enjoy the meal! | Buon appetito! | /ˌbwɔn appeˈtito/ |

| Goodbye! | Arrivederci (general) / Arrivederla (formal) / Ciao! (informal) | ( listen) /arriveˈdertʃi/ |

| Good luck! – Thank you! | Buona fortuna! – Grazie! (general) / In bocca al lupo! – Crepi [il lupo]! (to wish someone to overcome a difficulty, similar to "Break a leg!"; literally: "Into the wolf's mouth!" – "May the wolf die!") | |

| I love you | Ti amo (between lovers only) / Ti voglio bene (in the sense of "I am fond of you", between lovers, friends, relatives etc.) | /ti ˈvɔʎʎo ˈbɛne/ ; /ti ˈamo/ |

| Welcome [to...] | Benvenuto/-i (for male/males or mixed) / Benvenuta/-e (for female/females) [a / in...] | |

| Please | Per piacere / Per favore / Per cortesia | ( listen) |

| Thank you! | Grazie! (general) / Ti ringrazio! (informal) / La ringrazio! (formal) / Vi ringrazio! (plural) | ( listen) /ˈɡrattsje/ |

| You are welcome! | Prego! | /ˈprɛɡo/ |

| Excuse me / I am sorry | Mi dispiace (only "I am sorry") / Scusa(mi) (informal) / Mi scusi (formal) / Scusatemi (plural) / Sono desolato ("I am sorry", if male) / Sono desolata ("I am sorry", if female) | ( listen) /ˈskuzi/ ; /ˈskuza/ ; /mi disˈpjatʃe/ |

| Who? | Chi? | |

| What? | Che cosa? / Cosa? / Che? | |

| When? | Quando? | /ˈkwando/ |

| Where? | Dove? | /ˈdove/ |

| How? | Come? | /ˈkome/ |

| Why / Because | perché | /perˈke/ |

| Again | di nuovo / ancora | /di ˈnwɔvo/; /anˈkora/ |

| How much? / How many? | Quanto? / Quanta? / Quanti? / Quante? | |

| What is your name? | Come ti chiami? (informal) / Come si chiama? (formal) | |

| My name is ... | Mi chiamo ... | |

| This is ... | Questo è ... (masculine) / Questa è ... (feminine) | |

| Yes, I understand. | Sì, capisco. / Ho capito. | |

| I do not understand. | Non capisco. / Non ho capito. | ( listen) |

| Do you speak English? | Parli inglese? (informal) / Parla inglese? (formal) / Parlate inglese? (plural) | ( listen) /parˈlate.inˈɡlese/ |

| I do not understand Italian. | Non capisco l'italiano. | /nonkaˈpiskolitaˈljano/ |

| Help me! | Aiutami! (informal) / Mi aiuti! (formal) / Aiutatemi! (plural) / Aiuto! (general) | |

| You are right/wrong! | (Tu) hai ragione/torto! (informal) / (Lei) ha ragione/torto! (formal) / (Voi) avete ragione/torto! (plural) | |

| What time is it? | Che ora è? / Che ore sono? | |

| Where is the bathroom? | Dov'è il bagno? | ( listen) |

| How much is it? | Quanto costa? | /ˈkwanto ˈkɔsta/ |

| The bill, please. | Il conto, per favore. | |

| The study of Italian sharpens the mind. | Lo studio dell'italiano aguzza l'ingegno. |

Numbers

|

|

|

| English | Italian |

|---|---|

| one hundred | cento |

| one thousand | mille |

| two thousand | duemila |

| two thousand thirteen {2013} | duemilatredici |

Days of the week

| English | Italian | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| Monday | lunedì | /luneˈdi/ |

| Tuesday | martedì | /marteˈdi/ |

| Wednesday | mercoledì | /merkoleˈdi/ |

| Thursday | giovedì | /dʒoveˈdi/ |

| Friday | venerdì | /venerˈdi/ |

| Saturday | sàbato | /ˈsabato/ |

| Sunday | doménica | /doˈmenika/ |