Deepwater Horizon oil spill

Did you know...

The articles in this Schools selection have been arranged by curriculum topic thanks to SOS Children volunteers. SOS Children has looked after children in Africa for forty years. Can you help their work in Africa?

| Deepwater Horizon oil spill | |

|---|---|

The oil slick as seen from space by NASA's Terra satellite on May 24, 2010. |

|

| Location | Gulf of Mexico near Mississippi River Delta, United States |

| Coordinates | 28.736628°N 88.365997°W Coordinates: 28.736628°N 88.365997°W |

| Date | Spill date: 20 April – 15 July 2010 Well officially sealed: 19 September 2010 |

| Cause | |

| Cause | Wellhead blowout |

| Casualties | 13 dead (11 killed on Deepwater Horizon, 2 additional oil-related deaths) 17 injured |

| Operator | Transocean under contract for BP |

| Spill characteristics | |

| Volume | up to 4,900,000 barrels (210,000,000 US gallons; 780,000 cubic meters) Template error: {{ Convert}} no longer supports abbr=none. Use abbr=off instead. |

| Area | 2,500 to 68,000 sq mi (6,500 to 180,000 km2) |

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill (also referred to as the BP oil spill, the Gulf of Mexico oil spill, the BP oil disaster or the Macondo blowout) is an oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico which flowed for three months in 2010. The impact of the spill still continues even after the well was capped. It is the largest accidental marine oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry. The spill stemmed from a sea-floor oil gusher that resulted from the April 20, 2010 Deepwater Horizon explosion. The explosion killed 11 men working on the platform and injured 17 others. On July 15, the leak was stopped by capping the gushing wellhead, after it had released about 4.9 million barrels (780×103 m3), or 205.8 million gallons of crude oil. It was estimated that 53,000 barrels per day (8,400 m3/d) were escaping from the well just before it was capped. It is believed that the daily flow rate diminished over time, starting at about 62,000 barrels per day (9,900 m3/d) and decreasing as the reservoir of hydrocarbons feeding the gusher was gradually depleted. On September 19, the relief well process was successfully completed and the federal government declared the well "effectively dead".

The spill continues to cause extensive damage to marine and wildlife habitats as well as the Gulf's fishing and tourism industries. In late November 2010, 4,200 square miles (11,000 km2) of the Gulf were re-closed to shrimping after tar balls were found in shrimpers' nets. The total amount of Louisiana shoreline impacted by oil grew from 287 in July to 320 miles (510 km) in late November. In January 2011, eight months after the explosion, an oil spill commissioner reported that tar balls continue to wash up, oil sheen trails are seen in the wake of fishing boats, wetlands marsh grass remains fouled and dying, and that crude oil lies offshore in deep water and in fine silts and sands onshore.

Skimmer ships, floating containment booms, anchored barriers, sand-filled barricades along shorelines, and dispersants were used in an attempt to protect hundreds of miles of beaches, wetlands and estuaries from the spreading oil. Scientists have also reported immense underwater plumes of dissolved oil not visible at the surface as well as an 80-square-mile (210 km2) "kill zone" surrounding the blown BP well where "it looks like everything is dead" on the seafloor, according to independent researcher Samantha Joye.

The U.S. Government has named BP as the responsible party, and officials have committed to holding the company accountable for all cleanup costs and other damage. After its own internal probe, BP admitted that it made mistakes which led to the Gulf of Mexico oil spill.

Background

Deepwater Horizon drilling rig

The Deepwater Horizon was a 9-year-old semi-submersible mobile offshore drilling unit, a massive floating, dynamically positioned drilling rig that could operate in waters up to 8,000 feet (2,400 m) deep and drill down to 30,000 feet (9,100 m). The rig was built by South Korean company Hyundai Heavy Industries. It was owned by Transocean, operated under the Marshallese flag of convenience, and was under lease to BP from March 2008 to September 2013. At the time of the explosion, it was drilling an exploratory well at a water depth of approximately 5,000 feet (1,500 m) in the Macondo Prospect, located in the Mississippi Canyon Block 252 of the Gulf of Mexico in the United States exclusive economic zone about 41 miles (66 km) off the Louisiana coast. Production casing was being installed and cemented by Halliburton Energy Services. Once the cementing was complete, the well would have been tested for integrity and a cement plug set, after which no further activities would take place until the well was later activated as a subsea producer. At this point, Halliburton modelling systems were used several days running to design the cement slurry mix and ascertain what other supports were needed in the well bore. BP is the operator and principal developer of the Macondo Prospect with a 65% share, while 25% is owned by Anadarko Petroleum Corporation, and 10% by MOEX Offshore 2007, a unit of Mitsui. BP leased the mineral rights for Macondo at the Minerals Management Service's lease sale in March 2008.

Explosion

At approximately 9:45 p.m. CDT on April 20, 2010, methane gas from the well, under high pressure, shot all the way up and out of the drill column, expanded onto the platform, and then ignited and exploded. Fire then engulfed the platform. Most of the workers escaped the rig by lifeboat and were subsequently evacuated by boat or airlifted by helicopter for medical treatment; however, eleven workers were never found despite a three-day Coast Guard search operation, and are presumed to have died in the explosion. Efforts by multiple ships to douse the flames were unsuccessful. After burning for approximately 36 hours, the Deepwater Horizon sank on the morning of April 22, 2010.

Volume and extent of oil spill

An oil leak was discovered on the afternoon of April 22 when a large oil slick began to spread at the former rig site. According to the Flow Rate Technical Group the leak amounted to about 4.9 million barrels (205.8 million gallons) of oil exceeding the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill as the largest ever to originate in U.S.-controlled waters and the 1979 Ixtoc I oil spill as the largest spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

Spill flow rate

In their permit to drill the well, BP estimated the worst case flow at 162,000 barrels per day (25,800 m3/d). Immediately after the explosion BP and the United States Coast Guard did not estimate any oil leaking from the sunken rig or from the well. On April 24, Coast Guard Rear Admiral Mary Landry announced that a damaged wellhead was indeed leaking. She stated that "the leak was a new discovery but could have begun when the offshore platform sank ... two days after the initial explosion." Initial estimates by Coast Guard and BP officials, based on remotely operated vehicles as well as the oil slick size, indicated the leak was as much as 1,000 barrels per day (160 m3/d). Outside scientists quickly produced higher estimates, which presaged later increases in official numbers. Official estimates increased from 1,000 to 5,000 barrels per day (160 to 790 m3/d) on April 29, to 12,000 to 19,000 barrels per day (1,900 to 3,000 m3/d) on May 27, to 25,000 to 30,000 barrels per day (4,000 to 4,800 m3/d) on June 10, and to between 35,000 and 60,000 barrels per day (5,600 and 9,500 m3/d), on June 15. Internal BP documents, released by Congress, estimated the flow could be as much as 100,000 barrels per day (16,000 m3/d), if the blowout preventer and wellhead were removed and if restrictions were incorrectly modeled.

| Source | Date | Barrels per day | Gallons per day | Cubic metres per day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP estimate of hypothetical worst case scenario (assumes no blowout preventer) | Permit | 162,000 | 6,800,000 | 25,800 |

| United States Coast Guard | April 23 (after sinking) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BP and United States Coast Guard | April 24 | 1,000 | 42,000 | 160 |

| Official estimates | April 29 | 1,000 to 5,000 | 42,000 to 210,000 | 790 |

| Official estimates | May 27 | 12,000 to 19,000 | 500,000 to 800,000 | 1,900 to 3,000 |

| Official estimates | June 10 | 25,000 to 30,000 | 1,100,000 to 1,300,000 | 4,000 to 4,800 |

| Flow Rate Technical Group | June 19 | 35,000 to 60,000 | 1,500,000 to 2,500,000 | 5,600 to 9,500 |

| Internal BP documents hypothetical worst case (assumes no blowout preventer) | June 20 | up to 150,000 | up to 4,200,000 | up to 16,000 |

| Official estimates | August 2 | 62,000 | 2,604,000 | 9,857 |

Official estimates were provided by the Flow Rate Technical Group—scientists from USCG, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement, U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), and outside academics, led by United States Geological Survey (USGS) director Marcia McNutt. The later estimates were believed to be more accurate because it was no longer necessary to measure multiple leaks, and because detailed pressure measurements and high-resolution video had become available. According to BP, estimating the oil flow was very difficult as there was no underwater metering at the wellhead and because of the natural gas in the outflow. The company had initially refused to allow scientists to perform more accurate, independent measurements, saying that it was not relevant to the response and that such efforts might distract from efforts to stem the flow. Former Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency Carol Browner and Congressman Ed Markey (D-MA) both accused BP of having a vested financial interest in downplaying the size of the leak in part due to the fine they will have to pay based on the amount of leaked oil.

The final estimate reported that 53,000 barrels per day (8,400 m3/d) were escaping from the well just before it was capped on July 15. It is believed that the daily flow rate diminished over time, starting at about 62,000 barrels per day (9,900 m3/d) and decreasing as the reservoir of hydrocarbons feeding the gusher was gradually depleted.

Spill area and thickness

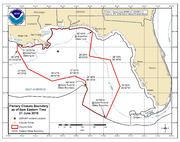

The oil's spread was initially increased by strong southerly winds caused by an impending cold front. By April 25, the oil spill covered 580 square miles (1,500 km2) and was only 31 miles (50 km) from the ecologically sensitive Chandeleur Islands. An April 30 estimate placed the total spread of the oil at 3,850 square miles (10,000 km2). The spill quickly approached the Delta National Wildlife Refuge and Breton National Wildlife Refuge. On May 19 both the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and other scientists monitoring the spill with the European Space Agency Envisat radar satellite stated that oil had reached the Loop Current, which flows clockwise around the Gulf of Mexico towards Florida and then joins the Gulf Stream along the U.S. east coast. On June 29, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration determined that the oil slick was no longer a threat to the loop current and stopped tracking offshore oil predictions that include the loop currents region. The omission is noted prominently on the ongoing nearshore surface oil forecasts that are posted daily on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration site.

On May 14, the Automated Data Inquiry for Oil Spills model indicated that about 35% of a hypothetical 114,000 barrels (18,100 m3) spill of light Louisiana crude oil released in conditions similar to those found in the Gulf would evaporate, that 50% to 60% of the oil would remain in or on the water, and the rest would be dispersed in the ocean. In the same report, Ed Overton says he thinks most of the oil is floating within 1 foot (30 cm) of the surface. The New York Times is tracking the size of the spill over time using data from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the US Coast Guard and Skytruth.

The wellhead was capped on July 15 and by July 30 the oil appeared to have dissipated more rapidly than expected. Some scientists believe the rapid dissipation of the surface oil may have been due to a combination of factors that included the natural capacity of the region to break down oil (petroleum normally leaks from the ocean floor by way of thousands of natural seeps and certain bacteria are able to consume it.); winds from storms appeared to have aided in rapidly dispersing the oil, and the clean-up response by BP and the government helped control surface slicks. As much as 40% of the oil may have simply evaporated at the ocean surface, and an unknown amount remains below the surface.

However, many scientists dispute the report's methodology and figures. Ronald Kendall, director of Texas Tech University's Institute of Environmental and Human Health, said, "I'm suspect if that's accurate or not; I'd like to say that even if it's true, there are still 50 to 60 million gallons [1.2 to 1.4 million barrels] that are still out there." Scientists said a lot of oil was still underwater and could not be detected. According to the NOAA report released on August 4, about half of the oil leaked into the Gulf remains on or below the Gulf's surface. Some scientists are calling the NOAA estimates "ludicrous." According to University of South Florida chemical oceanographer David Hollander, while 25% of the oil can be accounted for by burning, skimming, etc., 75% is still unaccounted for. The federal calculations are based on direct measurements for only 430,000 barrels (18,000,000 US gal) of the oil spilled — the stuff burned and skimmed. The other numbers are "educated scientific guesses," said Bill Lehr, an author of the NOAA report, because "it is impossible to measure oil that is dispersed". FSU oceanography professor Ian MacDonald called it "a shaky report" and is unsatisfied with the thoroughness of the presentation and "sweeping assumptions" involved. John Kessler of Texas A&M, who led a National Science Foundation on-site study of the spill, said the report that 75% of the oil is gone is "just not true" and that 50% to 75% of the material that came out of the well remains in the water in a "dissolved or dispersed form". On August 16, University of Georgia scientists said their analysis of federal estimates shows that 80% of that BP oil the government said was gone from the Gulf of Mexico is still there. The Georgia team said 'it is a misinterpretation of data to claim that oil that is dissolved is actually gone'.

In a December 3 statement, BP claimed the government overestimated the size of the spill. On the same day, presidential commission staff said that BP lawyers claim the size is overstated by between 20 and 50 percent. A document obtained by The Associated Press, submitted by BP to the commission, NOAA and The Justice Department, says, "They rely on incomplete or inaccurate information, rest in large part on assumptions that have not been validated, and are subject to far greater uncertainties than have been acknowledged. BP fully intends to present its own estimate as soon as the information is available to get the science right."

Oil sightings

Oil began washing up on the beaches of Gulf Islands National Seashore on June 1. By June 4, the oil spill had landed on 125 miles (201 km) of Louisiana's coast, had washed up along Mississippi and Alabama barrier islands, and was found for the first time on a Florida barrier island at Pensacola Beach. On June 9, oil sludge began entering the Intracoastal Waterway through Perdido Pass after floating booms across the opening of the pass failed to stop the oil. On June 23, oil appeared on Pensacola Beach and in Gulf Islands National Seashore, and officials warned against swimming for 33 miles (53 km) east of the Alabama line. On June 27, tar balls and small areas of oil reached Gulf Park Estates, the first appearance of oil in Mississippi. Early in July, tar balls reached Grand Isle but 800 volunteers were cleaning them up. On July 3 and July 4, tar balls and other isolated oil residue began washing ashore at beaches in Bolivar and Galveston, though it was believed a ship transported them there, and no further oil was found July 5. On July 5, strings of oil were found in the Rigolets in Louisiana, and the next day tar balls reached the shore of Lake Pontchartrain.

On September 10, it was reported that a new wave of oil suddenly coated 16 miles (26 km) of Louisiana coastline and marshes west of the Mississippi River in Plaquemines Parish. The Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries confirmed the sightings.

On October 23, it was reported that miles-long stretches of weathered oil had been sighted in West Bay, Texas between Southwest Pass, the main shipping channel of the Mississippi River, and Tiger Pass near Venice, Louisiana. The sightings were confirmed by Matthew Hinton of The Times-Picayune.

At the end of October, Scientists who were aboard two research vessels studying the spill's impact on sea life announced they had found substantial amounts of oil on the seafloor, contradicting statements by federal officials that the oil had largely disappeared. Kevin Yeager, a University of Southern Mississippi assistant professor of marine sciences found oil in samples dug up from the seafloor in a 140-mile (230 km) radius around the site of the Macondo well. The oil ranged from light degraded oil to thick raw crude, Yeager said. Yeager's team still needs to "fingerprint" the samples in labs to determine definitively that the oil came from BP's well. The sheer abundance of oil and its proximity to the well site, though, makes it "highly likely" that the oil is from the Macondo well, he said. A second research team also turned up traces of oil in sediment samples as well as evidence of chemical dispersants in blue crab larvae and long plumes of oxygen-depleted water emanating from the well site 50 miles (80 km) off Louisiana's coast.

In late November, Plaquemine Parish, Louisiana coastal zone director P.J. Hahn reported that more than 32,000 US gallons (760 bbl) of oil had been sucked out of nearby marshes in the previous 10 day period. In Barataria Bay, Louisiana, photos and first-hand accounts show oil still reaching high into the marshes, baby crabs and adult shrimp covered by crude and oil slicks on the surface of the water. "In some ways it's worse today," Hahn said, "because the world mistakenly thinks all the oil has somehow miraculously disappeared".

Underwater oil plumes

On May 15, researchers from the National Institute for Undersea Science and Technology, aboard the research vessel RV Pelican, identified oil plumes in the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico, including one as large as 10 miles (16 km) long, 3 miles (4.8 km) wide and 300 feet (91 m) thick in spots. The shallowest oil plume the group detected was at about 2,300 feet (700 m), while the deepest was near the seafloor at about 4,593 feet (1,400 m). Other researchers from the University of Georgia found that the oil may have occupied multiple layers. By May 27, marine scientists from the University of South Florida had discovered a second oil plume, stretching 22 miles (35 km) from the leaking wellhead toward Mobile Bay, Alabama. The oil had dissolved into the water and was no longer visible. Undersea plumes may have been the result of the use of wellhead chemical dispersants. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) conducted an independent analysis of the water samples provided from the 22–28 May research mission of the University of South Florida's Weatherbird II vessel. The samples from all undersea plumes were in very low concentrations, less than 0.5 parts per million. NOAA indicated that one of the plumes was unrelated to the BP wellhead leak, while the other plume samples were in concentrations too low or too highly fractionated to determine their origin. Reporting on a study that ended on June 28, scientists published conclusive evidence of a deep plume 22 miles (35 km) long linked directly to the Deepwater Horizon well. They reported that it did not appear to be degrading very fast and that it may pose a long-lasting threat for marine life deep in the ocean. On July 23, University of South Florida researchers and NOAA released two separate studies confirming subsea plumes of oil resulting from the Deepwater Horizon well. Researchers from NOAA and Princeton University concluded that the deep plumes of dissolved oil and gas would likely remain confined to the northern Gulf of Mexico and that the peak impact on dissolved oxygen would be delayed (several months) and long lasting (years).

David Valentine of the University of California, Santa Barbara believes that the oil plumes had been diluted in the ocean faster than they had biodegraded, suggesting that the LBNL researchers were overestimating the rate of biodegration. He did not challenge the finding that the oil plumes had dispersed.

When scientists initially reported the discovery of undersea oil plumes, BP stated its sampling showed no evidence that oil was massing and spreading in the gulf water column. NOAA chief Jane Lubchenco urged caution, calling the reports "misleading, premature and, in some cases, inaccurate." Researchers from the Universities of South Florida and Southern Mississippi claim the government tried to squelch their findings. "We expected that NOAA would be pleased because we found something very, very interesting," said Vernon Asper, an oceanographer at the USM. "NOAA instead responded by trying to discredit us. It was just a shock to us." Lubchenco rejected Asper's characterization, saying "What we asked for, was for people to stop speculating before they had a chance to analyze what they were finding." She argued for the necessity of chemically fingerprinting the plumes in order to distinguish them from oil seeps that occur naturally in the Gulf. In a report released on June 8, NOAA stated that one plume was consistent with the oil from the leak, one was not consistent, and that they were unable to determine the origin of two samples for certain.

On June 23, NOAA released a report which confirmed the existence of deepwater oil plumes in the Gulf and that they did originate from BP's well, citing a "preponderance of evidence" gathered from four separate sampling cruises. From the government's report: "The preponderance of evidence based on careful examination of the results from these four different cruises leads us to conclude that DWH-MC252 oil exists in subsurface waters near the well site in addition to the oil observed at the sea surface and that this oil appears to be chemically dispersed. While no chemical "fingerprinting" of samples was conducted to conclusively determine origin, the proximity to the well site and the following analysis support this conclusion".

In October 2010, scientists reported the presence of a continuous plume of over 35 kilometers in length at a depth of about 1100 meters. That plume persisted for several months without substantial degradation.

Oil on seafloor

On September 10, Samantha Joye, a professor in the Department of Marine Sciences at the University of Georgia on a research vessel in the Gulf of Mexico announced her team's findings of a substantial layer of oily sediment stretching for dozens of miles in all directions suggesting that a lot of oil did not evaporate or dissipate but may have settled to the seafloor. She describes seeing layers of oily material covering the bottom of the seafloor, in some places more than 2 inches thick atop normal sediments containing dead shrimp and other organisms. She speculates that the source may be organisms that have broken down the spilled oil and excreted an oily mucus that sinks, taking with it oil droplets that stick to the mucous. "We have to [chemically] fingerprint the oil and link it to the Deepwater Horizon," she says. "But the sheer coverage here is leading us all to come to the conclusion that it has to be sedimented oil from the oil spill, because it's all over the place."

By January 2011, USF researchers found layers of oil near the wellhead that were “up to 5 times thicker” than recorded by the team in August 2010. USF's David Hollander remarked, “Oil’s presence on the ocean floor didn’t diminish with time; it grew” and he pointed out, “the layer is distributed very widely,” radiating far from the wellhead.

Independent monitoring

Wildlife and environmental groups accused BP of holding back information about the extent and impact of the growing slick, and urged the White House to order a more direct federal government role in the spill response. In prepared testimony for a congressional committee, National Wildlife Federation President Larry Schweiger said BP had failed to disclose results from its tests of chemical dispersants used on the spill, and that BP had tried to withhold video showing the true magnitude of the leak. On May 19 BP established a live feed, popularly known as spillcam, of the oil spill after hearings in Congress accused the company of withholding data from the ocean floor and blocking efforts by independent scientists to come up with estimates for the amount of crude flowing into the Gulf each day. On May 20 United States Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar indicated that the U.S. government would verify how much oil had leaked into the Gulf of Mexico. Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lisa Jackson and United States Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano asked for the results of tests looking for traces of oil and dispersant chemicals in the waters of the gulf.

Journalists attempting to document the impact of the oil spill were repeatedly refused access to public areas and photojournalists were prevented from flying over areas of the gulf to document the scope of the disaster. These accusations were leveled at BP, its contractors, local law enforcement, USCG and other government officials. Scientists also complained about prevention of access to information controlled by BP and government sources. BP stated that its policy was to allow the media and other parties as much access as possible. On June 30, the Coast Guard put new restrictions in place across the Gulf Coast that prevented vessels from coming within “ of booming operations, boom, or oil spill response operations ”. In a press briefing, Coast Guard admiral Thad Allen said the new regulation was related to safety issues. On CNN's 360, host Anderson Cooper rejected the motivation for the restrictions outright.

In late June, reacting to the discovery of submerged oil plumes by the Universities of Alabama, and South Florida, BP's High Interest Technology Test (HITT) Team contracted with several independent researchers for the development of new technologies to detect, and map sub-sea dissolved oil plumes. By October, HITT team leader, Ken Lukins, was supervising tests of a variety of sensors off Mobile, Alabama's Dolphin Island. Systems included the CODA-Octopus Acoustic Sensor Array and a helicopter deployed submerged mass spectrometer/fluorescence hydrodynamic dart system created by engineer-pilot, Robert Tur. Both systems were successful, with the helicopter based testing capable of scanning, and 3D real-time mapping of up to 1,400 sq. miles, daily, while the ship-based CODA-Octopus Array was capable of high-resolution 3D scans, up to 120 feet, every 20 minutes. To date, despite both system's ability to prevent commercial fishermen from casting their nets in hydrocarbon plumes, neither system has been green lit by BP's Gulf Coast Restoration Organization (GCRO).

Efforts to stem the flow of oil

Short-term efforts

The first attempts to stop the oil spill were to use remotely operated underwater vehicles to close the blowout preventer valves on the well head; however, all these attempts failed. The second technique, placing a 125-tonne (280,000 lb) containment dome (which had worked on leaks in shallower water) over the largest leak and piping the oil to a storage vessel on the surface, failed when gas leaking from the pipe combined with cold water formed methane hydrate crystals that blocked the opening at the top of the dome. Attempts to close the well by pumping heavy drilling fluids into the blowout preventer to restrict the flow of oil before sealing it permanently with cement (" top kill") also failed.

More successful was the process of positioning a riser insertion tube into the wide burst pipe. There was a stopper-like washer around the tube that plugs the end of the riser and diverts the flow into the insertion tube. The collected gas was flared and oil stored on the board of drillship Discoverer Enterprise. 924,000 US gallons (22,000 barrels) Template error: {{ Convert}} no longer supports abbr=none. Use abbr=off instead. of oil were collected before removal of the tube. By June 3, BP removed the damaged riser from the top of the blowout preventer and covered the pipe by the cap which connected it to a riser. CEO of BP Tony Hayward stated that as a result of this process the amount captured was "probably the vast majority of the oil." However, the FRTG member Ira Leifer said that more oil was escaping than before the riser was cut and the cap containment system was placed.

On June 16, a second containment system connected directly to the blowout preventer became operational carrying oil and gas to the Q4000 service vessel where it was burned in a clean-burning system. To increase the processing capacity, the drillship Discoverer Clear Leader and the floating production, storage and offloading (FPSO) vessel Helix Producer 1 were added, offloading oil with tankers Evi Knutsen, and Juanita. Each tanker has capacity of 750,000 barrels (32,000,000 US gallons; 119,000 cubic metres) Template error: {{ Convert}} no longer supports abbr=none. Use abbr=off instead.. In addition, FPSO Seillean, and well testing vessel Toisa Pisces would process oil. They are offloaded by shuttle tanker Loch Rannoch.

On July 5, BP announced that its one-day oil recovery effort accounted for about 25,000 barrels of oil, and the flaring off of 57.1 million cubic feet (1.62×106 m3) of natural gas. The total oil collection to date for the spill was estimated at 660,000 barrels. The government's estimates suggested the cap and other equipment were capturing less than half of the oil leaking from the sea floor as of late June.

On July 10, the containment cap was removed to replace it with a better-fitting cap consisting of a Flange Transition Spool and a 3 Ram Stack ("Top Hat Number 10"). On July 15 BP tested the well integrity by shutting off pipes that were funneling some of the oil to ships on the surface, so the full force of the gusher from the wellhead went up into the cap. That same day, BP said that the leak had been stopped after all the blowout preventer valves had been closed on the newly fitted cap.

Considerations of using explosives

In mid-May, United States Secretary of Energy Steven Chu assembled a team of nuclear physicists, including hydrogen bomb designer Richard Garwin and Sandia National Laboratories director Tom Hunter. On May 24 BP ruled out conventional explosives, saying that if blasts failed to clog the well, "We would have denied ourselves all other options."

Permanent closure

Transocean's Development Driller III started drilling a first relief well on May 2 and was at 13,978 feet (4,260 m) out of 18,000 feet (5,500 m) as of June 14. GSF Development Driller II started drilling a second relief on May 16 and was halted at 8,576 feet (2,614 m) out of 18,000 feet (5,500 m) as of June 14 while BP engineers verified the operational status of the second relief well's blowout preventer. Each relief well is expected to cost about $100 million.

Starting at 15:00 CDT on August 3, first test oil and then drilling mud was pumped at a slow rate of approximately two barrels/minute into the well-head. Pumping continued for eight hours, at the end of which time the well was declared to be "in a static condition." At 09:15 CDT on August 4, with Adm. Allen's approval, BP began pumping cement from the top, sealing that part of the flow channel permanently.

On August 4, Allen said the static kill was working. Two weeks later, though, Allen said it was uncertain when the well could be declared completely sealed. The bottom kill had yet to take place, and the relief well had been delayed by storms. Even when the relief well was ready, he said, BP had to make sure pressure would not build up again. On August 19, Allen said that some scientists believe it is possible that a collapse of rock formations has kept the oil from continuing to flow and that the well might not be permanently sealed. The U.S. government wants the failed blowout preventer to be replaced in case of any pressure that occurs when the relief well intersects with the well. On September 3 at 1:20 p.m. CDT the 300 ton failed blowout preventer was removed from the well and began being slowly lifted to the surface. Later that day a replacement blowout preventer was placed on the well. On September 4 at 6:54 p.m. CDT the failed blowout preventer reached the surface of the water and at 9:16 p.m. CDT it was placed in a special container on board the vessel Helix Q4000. The failed blowout preventer will be taken to a NASA facility in Louisiana for examination.

On September 10, Allen said the bottom kill could start sooner than expected because a "locking sleeve" could be used on top of the well to prevent excessive pressure from causing problems. BP said the relief well was about 50 feet (15 m) from the intersection, and finishing the boring would take four more days. On September 16, the relief well reached its destination and pumping of cement to seal the well began.

On September 19, 2010, BP effectively killed the Macondo Well five months after the April 20th explosion. The relief well being drilled intersected the blown-out well Thursday September 16, and crews started pumping in cement on Friday September 17 to permanently plug it. Retired Coast Guard Adm. Thad Allen said, BP's well was "effectively dead." Allen said a pressure test to ensure the cement plug would hold was completed at 5:54 a.m. CDT. He added, "Additional regulatory steps will be undertaken but we can now state definitively that the Macondo Well poses no continuing threat to the Gulf of Mexico".

Efforts to protect the coastline and marine environments

The three fundamental strategies for addressing spilled oil were to; contain it on the surface, away from the most sensitive areas, to dilute and disperse it into less sensitive areas, and to remove it from the water. The Deepwater response employed all three strategies, using a variety of techniques. While most of the oil drilled off Louisiana is a lighter crude, the leaking oil was of a heavier blend which contained asphalt-like substances. According to Ed Overton, who heads a federal chemical hazard assessment team for oil spills, this type of oil emulsifies well. Once it becomes emulsified, it no longer evaporates as quickly as regular oil, does not rinse off as easily, cannot be eaten by microbes as easily, and does not burn as well. "That type of mixture essentially removes all the best oil clean-up weapons", Overton said.

On May 6, BP began documenting the daily response efforts on its web site. While these efforts began using only BP's resources, on April 28 Doug Suttles, chief operating officer, welcomed the US military as it joined the cleanup operation. The response increased in scale as the spill volume grew. Initially BP employed remotely operated underwater vehicles, 700 workers, four airplanes and 32 vessels. By April 29, 69 vessels including skimmers, tugs, barges and recovery vessels were active in cleanup activities. On May 4 the US Coast Guard estimated that 170 vessels, and nearly 7,500 personnel were participating, with an additional 2,000 volunteers assisting. On May 26, all 125 commercial fishing boats helping in the clean up were ordered ashore after some workers began experiencing health problems. On May 31, BP set up a call line to take cleanup suggestions which received 92,000 responses by late June, 320 of which were categorized as promising.

Containment

The response included deploying many miles of containment boom, whose purpose is to either corral the oil, or to block it from a marsh, mangrove, shrimp/crab/oyster ranch or other ecologically sensitive areas. Booms extend 18–48 inches (0.46–1.2 m) above and below the water surface and are effective only in relatively calm and slow-moving waters. More than 100,000 feet (30 km) of containment booms were initially deployed to protect the coast and the Mississippi River Delta. By the next day, that nearly doubled to 180,000 feet (55 km), with an additional 300,000 feet (91 km) staged or being deployed.

Some US lawmakers and local officials claimed that the booms didn't work as intended, saying there is more shoreline to protect than lengths of boom to protect it and that inexperienced operators didn't lay the boom correctly. Billy Nungesser, president of Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, said the boom "washes up on the shore with the oil, and then we have oil in the marsh, and we have an oily boom. So we have two problems”.

Barrier island plan

On May 21, Plaquemines Parish president Billy Nungesser publicly complained about the federal government's hindrance of local mitigation efforts. State and local officials had proposed building sand berms off the coast to catch the oil before it reached the wetlands, but the emergency permit request had not been answered for over two weeks. The following day Nungesser complained that the plan had been vetoed, while Army Corps of Engineers officials said that the request was still under review. Gulf Coast Government officials released water via Mississippi River diversions in an effort to create an outflow of water that would keep the oil off the coast. The water from these diversions comes from the entire Mississippi watershed. Even with this approach, on May 23, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted a massive landfall to the west of the Mississippi River at Port Fourchon. On May 23 Louisiana Attorney General Buddy Caldwell wrote to Lieutenant General Robert L. Van Antwerp of the US Army Corps of Engineers, stating that Louisiana had the right to dredge sand to build barrier islands to keep the oil spill from its wetlands without the Corps' approval, as the 10th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prevents the federal government from denying a state the right to act in an emergency. He also wrote that if the Corps "persists in its illegal and ill-advised efforts" to prevent the state from building the barriers that he would advise Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal to build the berms and challenge the Corps in court. On June 3 BP said barrier projects ordered by Adm. Thad Allen would cost $360 million. On June 16 Great Lakes Dredge and Dock Company under the Shaw Environmental and Infrastructure Group began constructing sand berms off the Louisiana coast.

By late October, the state of Louisiana had spent $240 million of the proposed $360 million from BP. The barrier had captured an estimated 1,000 barrels of oil, but critics and experts say the barrier is purely symbolic and call it "an exercise in futility" given the estimated five million barrels of oil in the gulf and the millions of dollars and man hours used to build the barrier. Many scientists say the remaining oil in the Gulf is far too dispersed to be blocked or captured by the sand structures. “It certainly would have no impact on the diluted oil, which is what we’re talking about now,” said Larry McKinney, head of the Gulf of Mexico research centre at Texas A&M University. “The probability of their being effective right now is pretty low.”

On December 16, a report by a presidential commission called the berms project "underwhelmingly effective, overwhelmingly expensive" because little oil appeared on the berms. However, the commission admitted the berm might help with reversing the effects of erosion on the coast. Jindal called the report "partisan revisionist history at taxpayer expense".

Dispersal

Spilled oil naturally disperses via storms, currents, and osmosis with the passage of time. Chemical dispersants accelerate the dispersal process, although they may have significant side-effects. Corexit EC9500A and Corexit EC9527A have been the principal dispersants employed. These contain propylene glycol, 2-Butoxyethanol and dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate. 2-butoxyethanol was identified as a causal agent in the health problems experienced by cleanup workers after the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill. Warnings from the Hazardous Substance Fact Sheet for 2-Butoxyethanol include "Cancer Hazard: 2-Butoxy Ethanol may be a carcinogen in humans since it has been shown to cause liver cancer in animals. Many scientists believe there is no safe level of exposure to a carcinogen" and "Reproductive Hazard: 2-Butoxy Ethanol may damage the developing fetus. There is limited evidence that 2-Butoxy Ethanol may damage the male reproductive system (including decreasing the sperm count) in animals and may affect female fertility in animals".

Corexit manufacturer Nalco states, "[COREXIT 9500] is a simple blend of six well-established, safe ingredients that biodegrade, do not bioaccumulate and are commonly found in popular household products....COREXIT products do not contain carcinogens or reproductive toxins. All the ingredients have been extensively studied for many years and have been determined safe and effective by the EPA". However, according to the OSHA-required Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDSs) for both versions of Corexit used in the Gulf, "Component substances have a potential to bioconcentrate" (or bioaccumulate), defined by the EPA as "accumulation of a chemical in tissues of a fish or other organism to levels greater than in the surrounding medium". The data sheets further state: "No toxicity studies have been conducted on this product".

Corexit EC9500A and EC9527A are neither the least toxic, nor the most effective, among the Environmental Protection Agency approved dispersants. They are also banned from use on oil spills in the United Kingdom. Twelve other products received better toxicity and effectiveness ratings, but BP says it chose to use Corexit because it was available the week of the rig explosion. Critics contend that the major oil companies stockpile Corexit because of their close business relationship with its manufacturer Nalco.

On May 1, two military C-130 Hercules aircraft were employed to spray oil dispersant. On May 7, Secretary Alan Levine of the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals, Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality Secretary Peggy Hatch, and Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Secretary Robert Barham sent a letter to BP outlining their concerns related to potential dispersant impact on Louisiana's wildlife and fisheries, environment, aquatic life, and public health. Officials requested that BP release information on their dispersant effects. The Environmental Protection Agency later approved the injection of dispersants directly at the leak site, to break up the oil before it reaches the surface, after three underwater tests. Independent scientists suggest that underwater injection of Corexit into the leak might be responsible for the oil plumes discovered below the surface. However, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration administrator Jane Lubchenco said that there was no information supporting this conclusion, and indicated further testing would be needed to ascertain the cause of the undersea oil clouds. By July 12, BP had reported applying 1,070,000 US gallons (4,100,000 l) of Corexit on the surface and 721,000 US gallons (2,730,000 l) underwater (subsea). The same document listed available stocks of Corexit which decreased by over 965,000 US gallons (3,650,000 l) without reported application, suggesting either stock diversion or unreported application. Under reported subsea application of 1,690,000 US gallons (6,400,000 l) would account for this discrepancy. Given the suggested dispersant to oil ratio between 1:10 and 1:50, the possible use of 1,690,000 US gallons (6,400,000 l) in subsea application could be expected to suspend between 400,000 to 2M barrels of oil below the surface of the Gulf.

On May 19, the Environmental Protection Agency gave BP 24 hours to choose less toxic alternatives to Corexit from the list of dispersants on the National Contingency Plan Product Schedule, begin applying the new dispersant(s) within 72 hours of Environmental Protection Agency approval or provide a detailed reasoning why the approved products did not meet the required standards. On May 20 US Polychemical Corporation reportedly received an order from BP for its Dispersit SPC 1000 dispersant. US Polychemical said it could produce 20,000 US gallons (76,000 l) a day in the first few days, increasing up to 60,000 US gallons (230,000 L) a day thereafter. Also on May 20, BP determined that none of the alternative products met all three criteria of availability, toxicity and effectiveness. On 24 May, Environmental Protection Agency administrator Jackson ordered the Environmental Protection Agency to conduct its own evaluation of alternatives and ordered BP to scale back dispersant use. According to analysis of daily dispersant reports provided by the Deepwater Horizon Unified Command, prior to May 26 BP used 25,689 US gallons (97,240 l; 21,391 imp gal) a day of Corexit. After the EPA directive, the daily average of dispersant use dropped to 23,250 US gallons (88,000 l; 19,360 imp gal) a day, a 9% decline. By July 30, more than 1.8 million gallons (6.8 million liters) of dispersant had been used, mostly Corexit 9500.

On July 31, Rep. Edward Markey, Chairman of the House Energy and Environment Subcommittee, released a letter sent to National Incident Commander Thad Allen, and documents revealing that the U.S. Coast Guard repeatedly allowed BP to use excessive amounts of the dispersant Coexit on the surface of the ocean. Markey's letter, based on an analysis conducted by the Energy and Environment Subcommittee staff, further showed that by comparing the amounts BP reported using to Congress to the amounts contained in the company’s requests for exemptions from the ban on surface dispersants it submitted to the Coast Guard, that BP often exceeded its own requests, with little indication that it informed the Coast Guard or that the Coast Guard attempted to verify whether BP was exceeding approved volumes. “Either BP was lying to Congress or to the Coast Guard about how much dispersants they were shooting onto the ocean,” said Rep. Markey.

On August 2, the EPA said dispersants did no more harm to the environment than the oil itself, and that they stopped a large amount of oil from reaching the coast by making the oil break down faster. However, independent scientists and EPA's own experts continue to voice concerns regarding the use of dispersants.

Dispersant use was said to have stopped after the cap was in place. Marine toxicologist Riki Ott wrote an open letter to the EPA in late August with evidence that dispersant use had not stopped and that it was being administered near shore. Independent testing supported her claim. New Orleans-based attorney Stuart Smith, representing the Louisiana-based United Commercial Fisherman’s Association and the Louisiana Environmental Action Network said he “personally saw C-130s applying dispersants from [his] hotel room in the Florida Panhandle. They were spraying directly adjacent to the beach right at dusk. Fishermen I’ve talked to say they’ve been sprayed. This idea they are not using this stuff near the coast is nonsense.”

Use of dispersants deep under water

Some 1,100,000 US gallons (4,200,000 l) of chemical dispersants were sprayed at the wellhead five thousand feet under the sea. This had never previously been tried but due to the unprecedented nature of this spill, BP along with the U.S. Coast Guard and the Environmental Protection Agency, decided to use "the first subsea injection of dispersant directly into oil at the source".

Dispersants are said to facilitate the digestion of the oil by microbes. Mixing the dispersants with the oil at the wellhead would keep some oil below the surface and in theory, allow microbes to digest the oil before it reached the surface. Various risks were identified and evaluated, in particular that an increase in the microbe activity might reduce the oxygen in the water. Various models were run and the effects of the use of the dispersants was monitored closely. The use of dispersants at the wellhead was pursued and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimated that roughly 409,000 barrels of oil were dispersed underwater.

Environmental scientists say the dispersants, which can cause genetic mutations and cancer, add to the toxicity of the spill and that sea turtles and bluefin tuna are exposed to an even greater risk than crude alone. According to them, the dangers are even greater for dispersants poured into the source of the spill, where they are picked up by the current and wash through the Gulf. University of South Florida scientists released preliminary results on the toxicity of microscopic drops of oil in the undersea plumes, finding that they may be more toxic than previously thought. The researchers say the dispersed oil appears to be having a toxic effect on bacteria and phytoplankton - the microscopic plants which make up the basis of the Gulf's food web. The field-based results were consistent with shore-based laboratory studies showing that phytoplankton are more sensitive to chemical dispersants than the bacteria, which are more sensitive to oil. On the other hand, the NOAA says that toxicity tests have suggested that the acute risk of dispersant-oil mixtures is no greater than that of oil alone. However, some experts believe that all the benefits and costs may not be known for decades.

Because the dispersants were applied deep under the sea, much of the oil never rose to the surface — which means it went somewhere else, said Robert Diaz, a marine scientist at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Va. "The dispersants definitely don't make oil disappear. They take it from one area in an ecosystem and put it in another," Diaz said. One plume of dipersed oil has been that measured at 22 miles (35 km) long, more than a mile wide and 650 feet (200 m) tall. The plume shows the oil "is persisting for longer periods than we would have expected," said researchers with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. "Many people speculated that subsurface oil droplets were being easily biodegraded. Well, we didn’t find that. We found it was still there". In a major study on the plume, experts found the most worrisome part to be the slow pace at which the oil is breaking down in the cold, 40 °F (4 °C) water at depths of 3,000 feet (910 m) 'making it a long-lasting but unseen threat to vulnerable marine life'. In September, Marine Sciences at the University of Georgia reported findings of a substantial layer of oily sediment stretching for dozens of miles in all directions from the capped well.

Removal

Three basic approaches to removing the oil from the water have been burning the oil, filtering off-shore, and collecting for later processing. On April 28, the US Coast Guard announced plans to corral and burn off up to 1000 barrels of oil each day. It tested how much environmental damage a small, controlled burn of 100 barrels did to surrounding wetlands, but could not proceed with an open ocean burn due to poor conditions.

BP stated that more than 215,000 barrels of oil-water mix had been recovered by May 25. In mid June, BP ordered 32 machines that separate oil and water with each machine capable of extracting up to 2000 barrels per day, BP agreed to use the technology after testing machines for one week. By June 28, BP had successfully removed 890,000 barrels of oily liquid and burned about 314,000 barrels of oil.

More recently the EPA reported that there were successful attempts made to contain the environmental impact of the oil spill, in which the Unified Command used the "situ burning" method to burn off the oil in controlled environments on the surface of the ocean to try and limit the environmental damages on the ocean as well as the shorelines. 411 controlled burn events took place, of which 410 could be quantified. Burning off an estimated 9.3 to 13.1 million gallons (220,000 to 310,000 barrels) on the ocean surface.

The Environmental Protection Agency prohibited the use of skimmers that left more than 15 parts per million of oil in the water. Many large-scale skimmers were therefore unable to be used in the cleanup because they exceed this limit. An urban myth developed that the U.S. government declined the offers because of the requirements of the Jones Act. This proved untrue and many foreign assets deployed to aid in cleanup efforts. The Taiwanese supertanker A Whale, recently retrofitted as a skimmer, was tested in early July but failed to collect a significant amount of oil. According to Bob Grantham, a spokesman for shipowner TMT, this was due to BP's use of chemical dispersants. The Coast Guard said 33 million gallons (790,000 barrels) of tainted water had been recovered, with 5 million gallons (120,000 barrels) of that consisting of oil. An estimated 11 million gallons (260,000 barrels) of oil were burned. BP said 826,000 barrels (131,300 m3) had been recovered or flared. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimated that about 25% of the oil had been removed from the Gulf. The table below presents the NOAA estimates based on an estimated release of 4.9 million barrels (780×103 m3) of oil (the category "chemically dispersed" includes dispersal at the surface and at the wellhead; "naturally dispersed" was mostly at the wellhead; "residual" is the oil remaining as surface sheen, floating tarballs, and oil washed ashore or buried in sediment). However, there is plus/minus 10% uncertainty in the total volume of the oil spill.

Two months after these numbers were released Carol Browner, director of the White House Office of Energy and Climate Change Policy, said they were "never meant to be a precise tool" and that the data "was simply not designed to explain, or capable of explaining, the fate of the oil... oil that the budget classified as dispersed, dissolved, or evaporated is not necessarily gone".

| Category | Estimate | Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct recovery from wellhead |

|

|

|

| Burned at the surface |

|

|

|

| Skimmed from the surface |

|

|

|

| Chemically dispersed |

|

|

|

| Naturally dispersed |

|

|

|

| Evaporated or dissolved |

|

|

|

| Residual remaining |

|

|

|

Based on these estimates, up to 75 percent of the oil from BP's Gulf oil disaster still remains in the Gulf environment, according to Christopher Haney, chief scientist for Defenders of Wildlife, who called the government report's conclusions misleading. Haney said. "Terms such as 'dispersed,' 'dissolved' and 'residual' do not mean gone. That's comparable to saying the sugar dissolved in my coffee is no longer there because I can't see it. By Director Lubchenco's own acknowledgment, the oil which is out of sight is not benign. Whether buried under beaches or settling on the ocean floor, residues from the spill will remain toxic for decades."

Appearing before Congress, Bill Lehr, a senior scientist at NOAA's Office of Response and Restoration, defended a report written by the National Incident Command (NIC) on the fate of the oil. This report relied on numbers generated by government and non-government oil spill experts, using an Oil Budget Calculator (OBC) developed for this spill. Based upon the OBC, Lehr said 6% was burned and 4% was skimmed but he could not be confident of numbers for the amount collected from beaches. As seen in the table above, he pointed out that much of the oil has evaporated or been dispersed or dissolved into the water column. Under questioning from congressman Ed Markey, Lehr agreed that the report said the amount of oil that went into the Gulf was 4.1m barrels, noting that 800,000 barrels were siphoned off directly from the well.

NOAA has been criticized by some independent scientists and Congress for the report's conclusions and for failing to explain how the scientists arrived at the calculations detailed in the table above. A formally peer reviewed report documenting the OBC is scheduled for release in early October. Markey told Lehr the NIC report had given the public a false sense of confidence. "You shouldn't have released it until you knew it was right," he said. Ian MacDonald, an ocean scientist at Florida State University, claims the NIC report "was not science". He accused the White House of making "sweeping and largely unsupported" claims that three-quarters of the oil in the Gulf was gone. "I believe this report is misleading," he said. "The imprint will be there in the Gulf of Mexico for the rest of my life. It is not gone and it will not go away quickly."

By late July 2010, two weeks after the flow of oil had stopped, oil on the surface of the Gulf had largely dissipated. Concern still remains for underwater oil and ecological damage.

In August, scientists had determined as much as 79 percent of the oil remains in the Gulf of Mexico, under the surface.

Oil eating microbes

In August a study of bacterial activity in the Gulf led by Terry Hazen of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, found a previously unknown bacterial species and reported in the journal Science that it was able to break down the oil without depleting oxygen levels. Hazen’s interpretation had its skeptics. John Kessler, a chemical oceanographer at Texas A&M University says “what Hazen was measuring was a component of the entire hydrocarbon matrix,” which is a complex mix of literally thousands of different molecules. Although the few molecules described in the new paper in Science may well have degraded within weeks, Kessler says, “there are others that have much longer half-lives — on the order of years, sometimes even decades.” He noted that the missing oil has been found in the form of large oil plumes, one the size of Manhattan, which do not appear to be biodegrading very fast.

By mid-September, research showed these microbes mainly digested natural gas spewing from the wellhead - propane, ethane and butane - rather than oil, according to a subsequent study published in the journal Science. David L. Valentine, a professor of microbial geochemistry at UC Santa Barbara, said that the oil-gobbling properties of the microbes had been grossly overstated.

Some experts have suggested that the proliferation of the bacteria may be causing health issues for residents of the Gulf Coast. Marine toxicologist Riki Ott says that the bacteria, some of which have been genetically modified, or otherwise bio-engineered to better eat the oil, might be responsible for an outbreak of mysterious skin rashes noted by Gulf physicians.

Consequences

Ecology

The spill is the 'worst environmental disaster the US has faced', according to White House energy adviser Carol Browner,. Indeed, the spill was by far the largest in US history, almost 20 times greater than the Exxon Valdez oil spill. However, the damage to the environment and the wildlife might be less in the Gulf due to various factors such as warmer water and the fact that the oil leaked deep under water. Factors such as petroleum toxicity, oxygen depletion and the use of Corexit dispersant are expected to be the main causes of damage. Eight U.S. national parks are threatened. More than 400 species that live in the Gulf islands and marshlands are at risk, including the endangered Kemp's Ridley turtle, the Green Turtle, the Loggerhead Turtle, the Hawksbill Turtle, and the Leatherback Turtle. In the national refuges most at risk, about 34,000 birds have been counted, including gulls, pelicans, roseate spoonbills, egrets, terns, and blue herons. A comprehensive 2009 inventory of offshore Gulf species counted 15,700. The area of the oil spill includes 8,332 species, including more than 1,200 fish, 200 birds, 1,400 molluscs, 1,500 crustaceans, 4 sea turtles, and 29 marine mammals.

As of November 2, 6,814 dead animals had been collected, including 6,104 birds, 609 sea turtles, 100 dolphins and other mammals, and 1 reptile. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, cause of death had not been determined as of late June. Also, dolphins have been seen which are lacking food, and "acting drunk" apparently due to the spill. A Mother Jones reporter kayaking in the area of Grand Isle reported seeing about 60 dolphins blowing oil through their blow holes as they swam through oil-slick waters.

Duke University marine biologist Larry Crowder said threatened loggerhead turtles on Carolina beaches could swim out into contaminated waters. Ninety percent of North Carolina's commercially valuable sea life spawn off the coast and could be contaminated if oil reaches the area. Douglas Rader, a scientist for the Environmental Defense Fund, said prey could be negatively affected as well. Steve Ross of UNC-Wilmington said coral reefs could be smothered. In early June Harry Roberts, a professor of Coastal Studies at Louisiana State University, stated that 4 million barrels (170,000,000 US gallons; 640,000 cubic metres) Template error: {{ Convert}} no longer supports abbr=none. Use abbr=off instead. of oil would be enough to "wipe out marine life deep at sea near the leak and elsewhere in the Gulf" as well as "along hundreds of miles of coastline." Mak Saito, an Associate Scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts indicated that such an amount of oil "may alter the chemistry of the sea, with unforeseeable results." Samantha Joye of the University of Georgia indicated that the oil could harm fish directly, and microbes used to consume the oil would also reduce oxygen levels in the water. According to Joye, the ecosystem could require years or even decades to recover, as previous spills have done. Oceanographer John Kessler estimates that the crude gushing from the well contains approximately 40% methane by weight, compared to about 5% found in typical oil deposits. Methane could potentially suffocate marine life and create dead zones where oxygen is depleted. Also oceanographer Dr. Ian MacDonald at Florida State University believes that the natural gas dissolving below the surface has the potential to reduce the Gulf oxygen levels and emit benzene and other toxic compounds. In early July, researchers discovered two new previously unidentified species of bottom-dwelling pancake batfish of the Halieutichthys genus, in the area affected by the oil spill. Damage to the ocean floor is as yet unknown.

In late July, Tulane University scientists found signs of an oil-and-dispersant mix under the shells of tiny blue crab larvae in the Gulf, indicating that the use of dispersants has broken up the oil into droplets small enough they can easily enter the food chain. Marine biologists from the University of Southern Mississippi's Gulf Coast Research Laboratory began finding orange blobs under the shells of crab larvae in May, and reportedly continue to find them "in almost all" of the larvae they collect from over 300 miles (480 km) of coastline stretching from Grand Isle, Louisiana, to Pensacola, Florida.

On September 29 Oregon State University researchers announced the oil spill waters contain carcinogens. The team had found sharply heightened levels of chemicals in the waters off the coast of Louisiana in August, the last sampling date, even after BP successfully capped its well in mid-July. Near Grand Isle, Louisiana, the team discovered that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons or PAHs, which are often linked to oil spills and include carcinogens and chemicals that pose various risks to human health, remained at levels 40 times higher than before the oil spill. Researchers said the compounds may enter the food chain through organisms like plankton or fish. The PAH chemicals are most concentrated in the area near the Louisiana Coast, but levels have also jumped 2 to 3 fold in other spill-affected areas off Alabama, Mississippi and Florida. As of August, PAH levels remained near those discovered while the oil spill was still flowing heavily. Kim Anderson, an OSU professor of environmental and molecular toxicology, said that based on the findings of other researchers, she suspects that the abundant use of dispersants by BP increased the bioavailability of the PAHs in this case. "There was a huge increase of PAHs that are bio-available to the organisms -- and that means they can essentially be uptaken by organisms throughout the food chain." Anderson added that exactly how many of these toxic compounds actually ended up in the food chain was beyond her area of research.

On October 22, it was reported that miles-long strings of weathered oil had been sighted moving toward marshes on the Mississippi river delta. Hundreds of thousands of migrating ducks and geese spend the winter in this delta.

Researchers reported in early November that toxic chemicals at levels high enough to kill sea animals extended deep underwater soon after the BP oil spill. Terry Wade of Texas A&M University, Steven Lohrenz of the University of Southern Mississippi and Stennis Space Centre found evidence of the chemicals as deep as 3,300 feet (1,000 m) and as far away as 8 miles (13 km) in May, and say the spread likely worsened as more oil spilled. The chemicals (PAHs), they said, can kill animals right away in high enough concentrations and can cause cancer over time. "From the time that these observations were made, there was an extensive release of additional oil and dispersants at the site. Therefore, the effects on the deep sea ecosystem may be considerably more severe than supported by the observations reported here," the researchers wrote in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. They added that PAHs include a group of compounds, and different types were at different depths, and said "It is possible they dissipate quickly, but no one has yet showed this".

In early November 2010, federally funded scientists found damage to deep sea coral several miles from BP's Macondo well. While tests are needed to verify that the coral died from the well, expedition leader Charles Fisher, a biologist with Penn State University, said, "There is an abundance of circumstantial data that suggests that what happened is related to the recent oil spill." According to the Associated Press, this discovery indicated that the spill's ecological consequences may be greater than what officials have said. Previous federal teams have stated that they found no damage on the ocean floor. "We have never seen anything like this," Fisher added. "The visual data for recent and ongoing death are crystal clear and consistent over at least 30 colonies; the site is close to the Deepwater Horizon; the research site is at the right depth and direction to have been impacted by a deep-water plume, based on NOAA models and empirical data; and the impact was detected only a few months after the spill was contained."

A Coast Guard report released on December 17 said that little oil remained on the sea floor except within a mile and a half of the well. The report said that since August 3, only 1 percent of water and sediment samples had pollution above EPA-recommended limits. Charlie Henry of NOAA warned even small amounts of oil could cause "latent, long-term chronic effects". And Ian R. MacDonald of Florida State University said even where the government claimed to find little oil, "We went to the same place and saw a lot of oil. In our samples, we found abundant dead animals."

Fisheries

In BP's Initial Exploration Plan, dated March 10, 2009, they said that "it is unlikely that an accidental spill would occur" and "no adverse activities are anticipated" to fisheries or fish habitat. On April 29, 2010, Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal declared a state of emergency in the state after weather forecasts predicted the oil slick would reach the Louisiana coast. An emergency shrimping season was opened on April 29 so that a catch could be brought in before the oil advanced too far. By April 30 the Coast Guard received reports that oil had begun washing up to wildlife refuges and seafood grounds on the Louisiana Gulf Coast. On May 22 The Louisiana Seafood Promotion and Marketing Board stated said 60 to 70% of oyster and blue crab harvesting areas and 70 to 80% of fin-fisheries remained open. The Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals closed an additional ten oyster beds on May 23, just south of Lafayette, Louisiana, citing confirmed reports of oil along the state's western coast.

On May 2 the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration closed commercial and recreational fishing in affected federal waters between the mouth of the Mississippi River and Pensacola Bay. The closure initially incorporated 6,814 square miles (17,650 km2). By June 21 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration had increased the area under closure over a dozen times, encompassing by that date 86,985 square miles (225,290 km2), or approximately 36% of Federal waters in the Gulf of Mexico, and extending along the coast from Atchafalaya Bay, Louisiana to Panama City, Florida. On May 24 the federal government declared a fisheries disaster for the states of Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana. Initial cost estimates to the fishing industry were $2.5 billion.

On June 23, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration ended its fishing ban in 8,000 square miles (21,000 km2), leaving 78,597 square miles (203,570 km2) with no fishing allowed, or about one-third of the Gulf. The continued fishing ban helps assure the safety of seafood, and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration inspectors have determined that as of July 9, Kevin Griffis of the Commerce Department said, only one seafood sample out of 400 tested did not pass, though even that one did not include "concerning levels of contaminants". On August 10, Jane Lubchenco of NOAA said no one had seen oil in a 8,000 square miles (21,000 km2) area east of Pensacola since July 3, so the fishing ban in that area was being lifted.

On August 31, a Boston lab hired by the United Commercial Fishermen's Association to analyze coastal fishing waters said it found dispersant in a seafood sample taken near Biloxi, Miss., almost a month after BP said it had stopped using the chemical.

According to the European Space Agency, the agency's satellite data was used by the Ocean Foundation to conclude that 20 percent of the juvenile bluefin tuna were killed by oil in the gulf's most important spawning area. The foundation combined satellite data showing the oil spill extent each week with data on weekly tuna spawning to make their conclusion. The agency also said that the loss of juvenile tuna was significant due to the 82% decline of the tuna's spawning stock in the western Atlantic during the 30 years prior to the oil spill.

Petroleum by-products found in Gulf seafood

A Florida TV station sent frozen Gulf shrimp to be tested for petroleum by-products after recent reports showed scientists disagreed on whether it is safe to eat after the oil spill. A private lab found levels of Anthracene, a toxic hydrocarbon and a by-product of petroleum, at twice the levels the FDA finds acceptable. The scientist who tested the shrimp said based on the results, she would not eat it, and that the results may surprise consumers and shrimpers.

A shrimp boat trawling waters north of the Deep Water Horizon well site hauled in a load of tar balls along with thousands of dollars' worth of shrimp, ruining the catch. The waters had been reopened to fishing on November 15. Due to this catch, on November 24 NOAA re-closed 4,200 square miles (11,000 km2) of Gulf waters to shrimping.

Tourism

Although many people cancelled their vacations due to the spill, hotels close to the coasts of Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama reported dramatic increases in business during the first half of May 2010. However, the increase was likely due to the influx of people who had come to work with oil removal efforts. Jim Hutchinson, assistant secretary for the Louisiana Office of Tourism, called the occupancy numbers misleading, but not surprising. "Because of the oil slick, the hotels are completely full of people dealing with that problem," he said. "They're certainly not coming here as tourists. People aren't sport fishing, they aren't buying fuel at the marinas, they aren't staying at the little hotels on the coast and eating at the restaurants."

On May 25 BP gave Florida $25 million to promote the beaches where the oil had not reached, and the company planned $15 million each for Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi. The Bay Area Tourist Development Council bought digital billboards showing recent photos from the gulf coast beaches as far north as Nashville, Tennessee and Atlanta. Along with assurances that the beaches were so far unaffected, hotels cut rates and offered deals such as free golf. Also, cancellation policies were changed, and refunds were promised to those where oil may have arrived. However, revenues remain below 2009 levels.

The U.S. Travel Association estimated that the economic impact of the oil spill on tourism across the Gulf Coast over a three-year period could exceed approximately $23 billion, in a region that supports over 400,000 travel industry jobs generating $34 billion in revenue annually.

On November 1 BP announced plans to spend $78 million to help Louisiana tourism and test and advertise seafood.

Other economic consequences

On July 5 BP reported that its own expenditures on the oil spill had reached $3.12 billion, including the cost of the spill response, containment, relief well drilling, grants to the Gulf states, claims paid, and federal costs. The United States Oil Pollution Act of 1990 limits BP's liability for non-cleanup costs to $75 million unless gross negligence is proven. BP has said it would pay for all cleanup and remediation regardless of the statutory liability cap. Nevertheless, some Democratic lawmakers are seeking to pass legislation that would increase the liability limit to $10 billion. Analysts for Swiss Re have estimated that the total insured losses from the accident could reach $3.5 billion. According to UBS, final losses could be $12 billion. According to Willis Group Holdings, total losses could amount to $30 billion, of which estimated total claims to the market from the disaster, including control of well, re-drilling, third-party liability and seepage and pollution costs, could exceed $1.2 billion.

On June 25 BP's market value reached a 1 year low. The company's total value lost since April 20 was $105 billion. Investors saw their holdings in BP shrink to $27.02, a nearly 54% loss of value in 2010. A month later, the company's loss in market value totalled $60 billion, a 35% decline since the explosion. At that time, BP reported a second-quarter loss of $17 billion, its first loss in 18 years. This includes a one-time $32.2 billion charge, including $20 billion for the fund created for reparations and $2.9 billion in actual costs.

BP announced that it was setting up a new unit to oversee management of the oil spill and its aftermath, to be headed by former TNK-BP chief executive Robert Dudley, who a month later was named CEO of BP.

On October 1, BP pledged as collateral all royalties from the Thunder Horse, Atlantis, Mad Dog, Great White, Mars, Ursa and Na Kika fields in the Gulf of Mexico. At that time, BP also said it had spent $11.2 billion, while the company's London Stock Exchange price reached 439.75 pence, the highest point since May 28.

By the end of September, BP reported that it had spent $11.2 billion. Third-quarter profit of $1.79 billion (compared to $5.3 billion in 2009) showed, however, that BP continues to do well and should be able to pay total costs estimated at $40 billion.

BP gas stations, the majority of which the company does not own, have reported sales off between 10 and 40% due to backlash against the company. Some BP station owners that lost sales say the name should change back to Amoco, while others say after all the effort that went into promoting BP, such a move would be a gamble, and the company should work to restore its image.

Local officials in Louisiana have expressed concern that the offshore drilling moratorium imposed in response to the spill will further harm the economies of coastal communities. The oil industry employs about 58,000 Louisiana residents and has created another 260,000 oil-related jobs, accounting for about 17% of all Louisiana jobs. BP has agreed to allocate $100 million for payments to offshore oil workers who are unemployed due to the six-month moratorium on drilling in the deep-water Gulf of Mexico.

The real estate prices and a number of transactions in the Gulf of Mexico area have decreased significantly since beginning of the oil spill. As a result, area officials want the state legislature to allow property tax to be paid based on current market value, which according to State Rep. Dave Murzin could mean millions of dollars in losses for each county affected.

The Organization for International Investment, a Washington-based advocate for overseas investment into the U.S., warned in early July that the political rhetoric surrounding the disaster is potentially damaging the reputation of all British companies with operations in the U.S. and sparked a wave of U.S. protectionism that has restricted British firms from winning government contracts, making political donations and lobbying.

Litigation